DISCLOSURE: AS AN AMAZON ASSOCIATE I EARN FROM QUALIFYING PURCHASES. READ THE FULL DISCLOSURE FOR MORE INFO. ALL AFFILIATE LINKS ARE MARKED #ad

If you’re like me, you probably love to nerd out over shots that totally reinvent what you thought was possible to capture on film. Recent films like Blade Runner 2049, High Life or The Joker come to mind, as do cinematic tv shows like Game of Thrones or Chernobyl.

Or what about iconic shots from auteur directors like the Coen brothers or David Fincher? Classic shots from cinema classics like The Godfather, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly or The Graduate might even be the reason you are a filmmaker or interested in videography today.

If you’ve ever been inspired after seeing one of those really awesome shots in a movie, then looked up how to recreate it on Google, you’re not alone. I’ve even done it! There are thousands of frequently asked questions about classic cinematic shots and how to recreate them online.

That’s why today we’re going to give you the answers to some of the most sought after video and film questions, telling you everything you need to know about the most frequently asked questions about camera shots and camera angles!

But first, some basics. If you already know about how camera shots and camera angles work, feel free to skip down to the Q&A portion by clicking here.

For those of you who want a refresher, let’s dive in:

Why are Camera Shots Important?

When it comes to the language of film, so much is communicated visually. That is, without any dialogue or text on the screen.

Yes, dialogue and title cards help tell a story, but it’s often everything else that does the lion’s share of the storytelling.

That’s because every decision that goes into the making of a film is a form of communication.

From the blocking of action to the design of the set to the casting and costumes and all the way down to the hair and make-up.

Every decision is communicating some part of the story to the audience, even if it’s just building the world of the setting around the characters.

The best movies and filmmakers consider every tiny detail possible and try to tie it back to how they can better tell their story.

If a character is in the background of a shot, what is that character communicating about the story? What is their costume communicating? What about the lamppost next to them? What about what they are holding, or what they are doing? You get the picture.

The Shot and The Frame

Speaking of pictures, no decision is more important to what is being communicated on screen than the shot. If you’re new to film or videography, the term “shot” simply refers to the placement and angle of the camera in relation to what is being shown in the frame.

Since film and video is essentially a series of photographs played at high speed to create the illusion of movement, the frame simply refers to everything seen on screen, while a shot is typically considered a series of frames all united by a set start point and a set endpoint for a set duration.

You can tell a shot has ended because there will be a cut to another angle. That means that if a camera is moving, it’s still part of the same shot until there’s an official cut.

It’s also why we as a filmmaker community have developed an obsession with “one-shots” and their duration. It can be quite tricky to film continuously for long durations and have everything go according to plan.

What are the types of camera shots?

There are all kinds of camera shots and camera angles, as there are many shorthand terms to describe them. I find it’s easiest to explain them by breaking them up into how they are defined:

Either by their distance in relation to a subject, angle in relation to a subject, or movement of the camera itself.

Camera Shots Defined By Distance

The camera shots that are defined by their distance from the subject are some of the most common shots you’ll see in film and tv. The one you’re probably most familiar with, even as a novice or regular audience member, is the close-up shot.

As you probably guessed, the term “close-up” refers to the camera’s distance being close to the subject. Close-ups are usually used to show the face of a character or an insert of an inanimate object for the purpose of highlighting that object’s significance.

For example, a close-up might be used as an insert to show one character handing a golden pocket watch to another character, highlighting the hands as they exchange the shimmering object.

Close-ups are used sparingly by master directors, used only when to communicate something very important.

Other common shots referred to by their distances from a subject include:

- full shots, referring to a shot featuring the full subject is seen in the frame

- medium shots, featuring the top half of a subject in the frame

- medium-close-up shots, featuring the head and shoulders of a subject in the frame

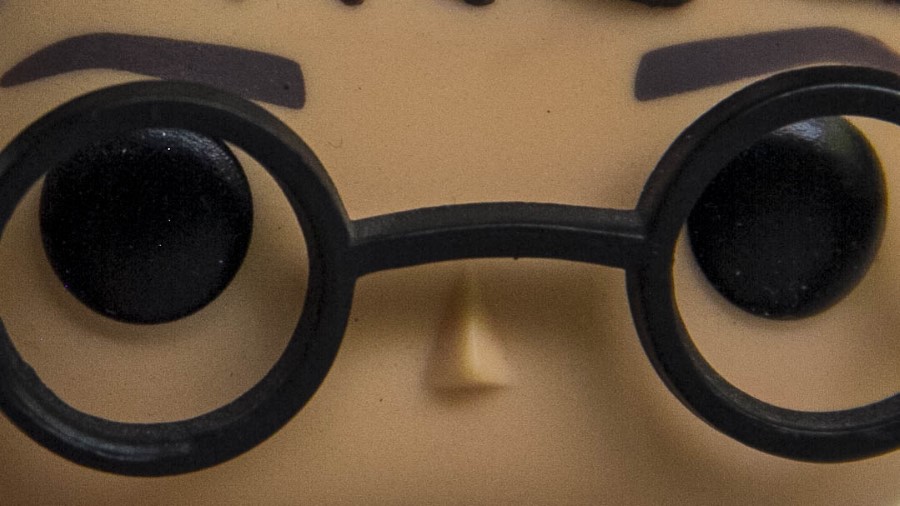

- extreme close-up shots, featuring an extremely close-up view of a subject in the frame.

In the case of an extreme close up, think of something specific, like a pair of dilated eyes, a sniffling nose, pursed lips or twitching fingers. Like a regular close-up, this type of shot is used best sparingly – to show extremely minute details that are important to the story that the audience might otherwise miss.

There are also wide shots, where the subject is far enough away from the camera that you can see it in its entirety in relation to their surroundings, as well as long shots and extreme long shots, where subjects are so far away they are dwarfed by the surroundings around them.

As mentioned above, all of these shots are united in their depiction of how far away the subject is from the camera, and are some of the most commonly used on film.

Classically, most scenes between one or more characters in conversation follow a standard formula of moving closer and closer in as the drama of the scene gets more and more intense.

For example, a scene would start with a wide shot or long shot, often referred to in this context as an establishing shot, then move into a full shot and / or then to medium shot, and finally to a close-up shot, and if called for, even an insert of an extreme close up.

If you’ve ever seen a shot list before, you might have seen some of these terms written out in shorthand. Knowing the terms, it should be fairly straightforward to understand what shots these terms are referring to:

- FS – Full shot.

- WS – Wide shot

- LS – Long shot

- CU – Close-up

- MED – Medium

- MCU – Medium close-up

- ECU – Extreme close-up

Camera Shots Defined By Angle

After your standard shots that are defined by the camera’s distance from a subject, we get into shots that are defined by the camera’s angle on the subject.

The most common shot used in this category is the over-the-shoulder shot, which refers to any shot where the camera is placed over the shoulder of a person or object that is obstructing the frame.

For example, a scene between two people could be shot using over the shoulders, where the camera is over the shoulder of one person while the other one is talking. This creates a more intimate feeling as if you as the viewer are in the middle of the scene.

Over-the-shoulder shots can also be used with long lenses to create a feeling that you are actually spying on the characters in the scene. This can be a great technique to use when filming horror or thriller-style scenes where you want the dialogue scenes to feel unnerving.

Shots Defined by the Number of People in the Frame

Similar to the over-the-shoulder shot, there are also shorthand terms for shots depending on how many subjects are captured by the angle of the camera.

For example, a single-shot would describe an angle where only one character is caught in the frame, while a two-shot describes a frame with two characters in it, and a three-shot describes a character with three characters in it.

Other shots defined by their angle include low-angle and high-angle shots, which quite literally describe when a camera is placed below a subject looking up at them, or when the camera is above the subject looking down on them.

These camera angles are usually used for a specific purpose. For example, a low angle shot usually implies the subject is powerful or trying to seem like they are, while a high angle can imply that the subject is weak or insecure.

While those terms are more literal, there are also more figurative shots, including shots like the birds-eye-view shot, where the camera takes a high position in the sky looking down on a subject, or a point-of-view shot, where the camera quite literally takes on the position of one of the subjects to put the audience in that subject’s point of view.

Then there’s the dutch angle, which is defined as any angle that is diagonal or off its axis. The dutch angle shot is meant to imply that something is really wrong in the story.

Since looking at an image that is askew can be disorienting, the angle is meant to have a disorienting effect. This shot is often used in suspenseful thrillers or psychological horror movies but can be used quite masterfully in straight comedic and dramatic films as well.

Camera Shots Defined By Movement

Lastly, there are camera shots that are referred to by the way the camera is moving. Normal camera angles often refer to static shots, where the camera is on a tripod and relatively still.

The most well-known shot in this category is the zoom shot. Zoom shots are shots where the camera lens zooms in on or zooms out from, a subject in the frame.

Everyone who has ever picked up a still photography camera or owned a smartphone has used the zoom feature of their lens.

While a very commonplace type of camera movement, it creates a very specific effect in film and television and is used somewhat sparingly in dramatic storytelling, reserved for more comedic or over the top moments.

Zooms can be used in dramatic or thriller movies more overtly, like if a camera has taken the point of view of another lens, like a telescope or binoculars.

Zooms are also used in subtle ways, to subtly enforce or highlight key moments or details during a long take – usually, if a character is monologuing.

Other types of shots labeled by their type of movement include tracking shots, where a camera is physically tracking a subject along a set path, tilting shots, where a camera is stationary but tilts up or down to with a subject, and panning shots, where a camera is in a set position on a tripod but panning to the left or right with a subject.

Moving Shots Defined by What They’re Mounted On

Moving camera shots are also labeled more specifically by what device they are being moved on.

As an example, a dolly shot refers to a tracking shot that is created using a dolly, while a crane shot refers to the camera being moved all-around via a crane, and a steadicam, gimbal or handheld shot refers to the camera being operated with a steadicam rig, a gimbal or in a handheld, loose and free-moving manner.

There’s also a smaller crane-like device known as a jib, which works like a see-saw with a counter-weight on one end and the camera on the other. Shots taken with a jib are referred to as jib shots.

Taking this labeling system further, if you are getting an aerial shot with a drone, you would call that a drone shot, and if your film or video shoot has an unlimited budget, you could even get a helicopter shot, though you could also accurately label either shot as a birds-eye view shot.

If you are less specific on the type of move your camera is taking, you might refer to a dolly or tracking shot as a push in or push out. A push in would be if you are moving the camera forward towards a subject, while a push out would be the reverse.

These shots are often used in place of a zoom, because they are smoother and less noticeable, and are always a nice touch to heighten the drama or excitement of a scene, especially during moments where the camera would otherwise be stationary, like a scene with two characters talking.

How do camera angles tell a story?

Any director who makes informed choices when blocking, shot-listing, and shooting a scene will always consider what each shot means in relation to the story.

Coverage refers to all the shots you plan to capture to cover an entire scene, and while many directors like to have enough coverage to give the editor flexibility in the way they edit the scene, a good director will usually cover the scene in a way that best communicates how they want the story told.

Getting more specific, how can a camera angle or shot tell a story? Here’s an example:

Let’s say you choose to feature a subject in the middle of a large sweeping landscape with a long shot. Whether you meant to or not, you are indicating that a character is overwhelmed by the odds or the environment around them.

Think of a shot where a character looks as if they are being swallowed up by a giant desert, or miles from safety on a treacherous mountain pass.

A point of view shot, meanwhile, would be used to put the audience in the shoes (or quite literally, eyes) of a character to see what they are seeing.

This type of shot can be used to help communicate important plot details but plays a more subtle role in getting the audience to identify with the main character if used appropriately.

In the case of a thriller or horror movie, a point of view shot might be introducing a new character who could represent a threat to the characters we already know and can be used in very creepy and unsettling ways.

Even the traditional full, medium and close-up shots can be deployed strategically to communicate narrative choices about the characters and story – especially in the hands of a masterful director.

Speaking of masterful directors, this video from Every Frame a Painting does a great job of breaking down how Mindhunter and House of Cards director David Fincher use certain shots to communicate his stories:

Speaking in classic cinema language, a full shot is often used when introducing a new character to the world, while a close-up would be used when we get a new insight or emotional monologue from a character we already know.

In fact, every choice an editor makes in putting together the separate shots of a scene, including the order those shots are used in, can communicate so much about what is happening in that scene.

While a classical set-up might start with a master or establishing shot and get closer in as the scene heats up, by starting with a close-up and then going out wider and wider you can reveal a lot more and tell a much different story than you would do it the opposite way.

When choosing what coverage to capture on any given film shoot, you should consider both what you are trying to communicate as well as what the audience expects you to communicate.

As an example, if you were to shoot a whole movie in close-ups, it might be disorienting for viewers who expect to at some point see the world outside of your character’s point of view.

Frequently Asked Questions About Camera Shots

Now that we’ve gotten the basics out of the way, let’s dive into some of the most asked questions about camera shots, and our answers!

What are the most commonly used shots in film?

The most commonly used shots in film are the standard long, medium, and close-up shots.

This is partly because these shots are the simplest ingredients necessary to tell a story, and partially because certain shots that fall into the category or long, medium or close are also another type of shot, like a medium two-shot or a low-angle close-up shot.

But let’s get more specific about why these three types of shots are used at all.

First, the long shot. A long shot (or wide shot) establishes the environment around a scene. It establishes the setting and establishes the space in which we imagine the rest of the world taking place.

These establishing shots are important because they help the audience believe in the reality of the story and the world of the characters, and also establish the rule of the environment.

If a character chases another character down a hallway, for example, a long shot might help provide a sense of how long the hallway is, setting the stakes for the chase. If we see in a long shot that the hallway is actually a bridge suspended over lava, that changes the stakes of the chase scene entirely.

The medium shot, on the other hand, is used more commonly than almost any other shot because it provides a middle ground between a long shot and a close-up as that character interacts with the world around it.

Usually shot from the waist up, mediums are close enough to show the character’s actions as they interact with the world around them, and from a far enough away distance that we aren’t isolated from that same world.

Close-ups, meanwhile, are important because of how they convey information, either by highlighting important details or highlighting important emotions.

The closer we are to a subject physically, the closer we feel to them emotionally, and the more likely we will be to identify with them and their words and feelings.

Close-ups also focus us squarely on one character or one subject. Just as if you were leaning in to get a better look at something or hear someone better, when close-ups are used, they subconsciously tell us to pay attention. If it’s big on-screen, it’s probably a big deal.

These three shots combined are enough to tell a story; adding other elements, like pointed angles or movements merely heightens and adds to the specificity of the storytelling of the director.

What is the Difference Between a Long Shot and a Wide Shot?

A wide shot and a long shot are often synonymous. While they create somewhat different effects, they are often used in similar contexts.

For example, when we were just referring to long shots being used to establish a space, you could just as easily substitute a long shot for a wide shot and it would convey the same information.

The main difference between a wide shot and a long shot in this context is the lens you are using to shoot with.

For example, an establishing wide would be shot on a wide lens, while an establishing long would be shot on a long lens.

While a long shot will show you a subject in relation to the environment around them from a distance, a wide shot will show you a subject in relation to the environment around them, but usually at the same distance as that environment.

In this instance, it really is the difference between how wide a frame goes that determines whether it is a wide shot or a long shot.

In a long shot, you would see the subject dwarfed standing down a long street, while a wide shot would show you the subject dwarfed next to a large warehouse.

What is a dynamic shot?

A dynamic shot is a shot where the angle or position of the camera changes in the middle of the shot, as opposed to a static shot, where a camera stays in one place and stays focused on one angle.

Moving shots like push-ins or tracking shots are dynamic shots, but a tilt or a pan also qualify, since the angle of the camera is changing.

Even if the camera is technically in the same position, but it changes its angle slightly to focus on another character or another detail in the scene, that shot is a dynamic shot.

If a camera stays in the same position and the frame around a subject stays exactly the same from beginning to end, the shot is a static shot and not a dynamic shot.

What are the basic types of camera movement?

As we mentioned above, a zoom shot is the most basic type of camera movement that anyone with a camera knows how to do. Zooming shots create the illusion of moving closer to a subject while the camera itself stays in the same spot.

Then you have dollying and tracking, which refers to when you move a camera physically closer or farther away from a subject.

Dollying is another term for pushing towards or away from a subject, while tracking is another term for following a subject.

You also have tilting and panning, which refer to movements where the camera stays stationary but you move the camera’s point of view. In the case of tilting, you are moving the camera angle up and down, while in the case of panning you are moving it left or right.

Lastly, you have handheld shots, referring to any type of camera movement done using a steadicam or handheld rig.

These shots might not always make big movements, but because they aren’t on a tripod or mounted to something else, there is an inherent camera movement in the frame even when shooting a medium close-up of a subject.

There are also aerial movements, crane movements, jib movements, and even truck movements, but these are more common to higher budget productions, like helicopters, cranes, and car mounts can be quite expensive.

Why are Mid Shots used?

Mid shots, in this instance, referring to medium shots, are used most often for scenes that include a lot of dialogue or conflict between two or more characters.

While a close-up might reveal a single character’s feelings better, a medium shot would better communicate their body language in relation to another character.

Is the character squeamish around this other character because they are nervous, or confidently spreading out and leaning back at ease?

Medium shots are also good at communicating with the audience how the characters feel in relation to the environments they inhabit.

Is a character at home and bouncing around from one room to another, or are they trying to make themselves as small as possible in a little chair in the center of an overwhelming and foreign room around them?

Also, a good scene between two characters will include a lot of action, even if the action is subtle, and meant to underscore the unspoken conflict between the two characters.

Wide shots are good at establishing spaces and showing big changes in blocking, while medium shots, especially dynamic medium shots that track or pan with characters, are good at keeping scenes active in smaller, more subtle ways.

Lastly, medium shots, especially medium shots at an eye-level angle, are good at establishing an emotionally neutral tone to a scene.

If the point of a scene is to establish exposition and convey information the audience needs to understand in order for the story to continue, then medium shots are a good way for the audience to pay attention to what’s being communicated in a straight forward, emotionally neutral tone.

What Does an Eye-Level Camera Angle do?

An eye-level camera angle is any shot that is positioned at eye-level with the subject, as opposed to high or low angle shots that are below or above the subject’s eye line.

Eye-level angle shots are really common because of how neutral they are – almost like the default way to angle a shot.

That’s because being eye-level feels natural. If you are having a conversation with someone at eye-level in real life, you are usually facing them head-on, probably while sitting down across from them at a table, creating a stationary and comfortable tone to the conversation.

Shots angled at eye level create the same effect, whether they are at a full length, medium, or close-up distance, and are thought to be the best for conveying information in a straightforward way.

If two characters are talking and the camera is covering them at eye level, it’s usually because the information is shared between them is more important than the dramatic tension of that moment.

Why is a Two-Shot used?

As mentioned briefly above, a two-shot is any shot featuring two subjects in the frame.

While two characters having a conversation with each other is usually shot in a shot-reverse-shot type of coverage, there are times where you might want to cover two of your characters in a scene in the same shot.

This could be because the two characters are confronting another character together. Or two characters in opposition to one another are forced close together due to an environmental factor, like a closed elevator or a crowded room.

Maybe two characters are romantically interested in each other, and as they grow closer and closer together, you want to bring them physically together into the same frame.

Or they could be two adversaries fighting to the death, and as they each struggle harder and harder to stay alive, they are forced into the same frame, ratcheting up the tension and intensity of their fight.

Two shots are also good for comedic effect and comedic timing, especially if two characters are foils to one another or two peas in a comedic pod. Witty banter can fly back and forth, or two comedic characters can lob one-liners from the sidelines.

These shots are especially useful in situations where your actors are doing a lot of improvisation, as it makes editing unscripted content much easier.

Lastly, if you use a two-shot in a group scene, you can show the battle lines between two opposing sides, and can even do your coverage in a shot-reverse-shot style with two opposing two shots.

The same is true of a three-shot, which we’ll get into below.

What is a Three-Shot?

A three-shot is a shot that refers to the number of people featured in the frame. Similar to a two-shot, a three-shot features three subjects instead of just two.

This shot is used most often when a group of characters is meant to be overwhelming or overpowering a single character, or if two groups of rival characters are facing off, and showing the breadth of their emotions or diversity of expression is important in telling the story.

For example, you might want to use a three-shot in a scene where your character is pitching an idea to three higher-level executives at their company.

This would highlight how the character is overwhelmed, anxious, and staring down a wall of opposition – especially if the executives are deadpan while the character delivers their heartfelt, passionate plea.

In contrast, you might not want to use a three-shot in a scene where four main characters are debating a complicated issue or in the middle of a heated argument and are all on opposing sides.

What you could do when facing that very specific scenario, is to use a three-shot for a moment in your story when three of the characters finally agree, and one character does not.

This will highlight the power imbalance, especially if used at a moment where, up until that point, your coverage featured a series of changing medium and two shots depending on whichever characters were aligning or breaking apart with one another over the course of the scene.

Why are different camera angles used?

Besides the obvious answers, like because a movie is made up of multiple scenes at multiple locations, or because it’s insanely difficult to pull off one-takes even for ten minutes, let alone the entire length of a feature, the answer is this: you need to use different camera angles to refocus the audience on what is most important to tell the story at different moments.

This could be for technical reasons; maybe you can’t fit everyone with a line of dialogue in a scene in the same frame.

Maybe the set you are using is confined and you need to flip the camera around to see the rest of the scene. Maybe you need to show something really important that’s close-up.

More often, though, this is for directorial reasons; you want to tell the story in a specific way.

You want the audience to see what you saw when you read the script, or when you wrote the script:

You want to convey a certain look or feel.

You want to convey important information.

You want to communicate the drama without dialogue, or in between the dialogue.

You want to put us in the shoes of the character or feel what they are feeling, or see what they are seeing.

Maybe you want the camerawork to push the limits of what’s been done before with new camera angles.

Maybe you want the camerawork to feel like no camera is there at all.

Even if you are filming your entire feature film in one take, you will inevitably move the camera to various angles to better capture and relay the story to your audience.

You might track from room to room with a character, or leave one character to follow another, or change the frame to focus on different characters in the same room.

Because film and video are rooted in still photography, each individual frame of every individual shot tells its own story. When you use different angles you are telling a different part of your story – even in the changing from one angle to another in the same shot.

How do camera angles affect the audience?

Camera angles affect the audience in many different ways. As we’ve reviewed above, camera angles can change the way the audience views a character, both how they physically view the character and how they emotionally view the character.

Above we used the example of how a point of view shot can put the audience in the point of view of a character.

But if we view a character from a birds-eye view angle, that can separate us from the character emotionally. We might now see them more as a cog in a larger machine, or just a face in the crowd, or as something to be pitied or observed, but not connected to.

If we shift back into a close-up on the character in another scene, we might begin to emotionally connect with that character again, but going directly from a birds-eye view shot to a close-up shot could have a very disorienting effect.

Putting some full shots and wide shots and medium shots in between them can have a less jarring and more effective result. In this instance, different camera angles help to smooth over transitions between beats or scenes.

In a very real way, camera angles help us by shaping the way the audience interacts with and experiences the story. The same scene, if viewed from another angle, or various other angles, could play very differently to an audience.

Think about the example I just shared about how two shots and three shots impact the dynamics between characters.

The audience might feel that three characters are against one other character if shot in a three-shot, while the same scene might feel that two pairs of characters are facing off against one another if shot in two separate two shots.

On a macro-level, all camera angles affect the audience emotionally by informing their point of view of that story. On a micro-level, each camera angle affects the audience differently.

Understanding how each individual angle will affect the audience’s perception of the story at any given moment is one of the most important jobs of the director. Hopefully, you can use the guide above as a shorthand to do so.

As a camera moves in position, the viewer is moved to see the characters and relationships between them in a new position.

In this way, camera angles shape the way we understand a film, and in ways sometimes overt and sometimes subtle, shape the entire meaning of a film.

That’s why knowing the different camera shots and camera angles, as well as how to use them, is as important to how you make your movie as whatever camera you film them with.

Different Camera Shots and Camera Angles Matter!

We hope those answers help clear up most of your camera angle and camera questions.

If you have more, send them our way, and we’d love to answer them in another article!

Until then, good luck with creating your next project!

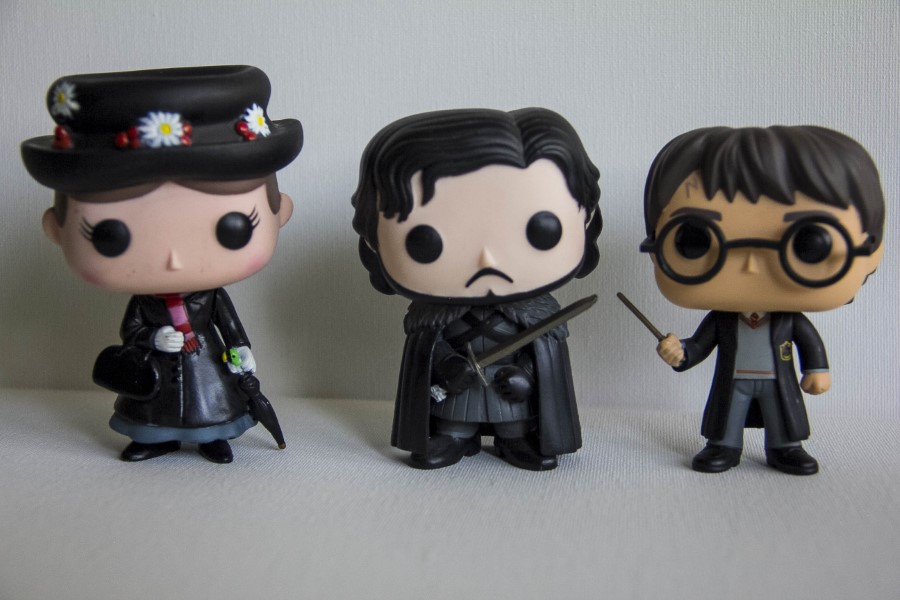

this article would have been much more interesting and better to understand if you had included examples of all those shots from actual film scenes along with the ones with the toys