Writing a screenplay for a short film involves condensing the traditional structure of a screenplay into a shorter format, usually ranging from 5 to 30 minutes in length.

The process includes several steps:

1. Conceptualize Your Story:

Brainstorm ideas for your story. What message or emotion do you want to convey?

Decide on the genre and tone of your short film.

Consider the constraints of a short film, such as limited locations, characters, and dialogue. Horror films can be a good place to start.

Develop a central conflict or a unique premise. Dan Harmon’s story circle is a good place to start.

2. Outline Your Story:

Create a basic outline that breaks down your story into the beginning, middle, and end.

Identify the main plot points and pivotal moments.

Determine the character arcs and how they will change or learn something by the film’s end.

Read more on outlining in the article How to Write a Screenplay That Works.

3. Write a Treatment:

Expand on your outline to create a treatment, a short narrative of your story, written in the present tense and describing the events as they happen.

This helps you visualize the film and serves as a guide for your screenplay.

Here’s a guide with examples of how to write a film treatment.

4. Structure Your Short Film:

Short films follow the same narrative structure as any story. But when writing a short film, you don’t have time for, nor do you need, as many story beats as a feature film.

The same ups and downs that make feature films so interesting aren’t necessary or possible in a short film.

In a feature film, the character is in a comfort zone but wants something and enters an unfamiliar situation. This can take up to 30 minutes of build-up, sometimes less, sometimes more.

In a short film, this should happen in 3 minutes or less. The best short films often set up what a character wants within the first 30 seconds of the film, and within at least a one to two-minute window, they are thrust into an unfamiliar situation to get it.

The three-act structure (setup, confrontation, resolution) can still apply to short films but must be condensed.

The Hollywood Model also provides a good visual outline for a script.

Focus on one or two key scenes, to begin with, that encapsulate your story and work out from those.

Ensure that every scene and line of dialogue serves and moves the story forward.

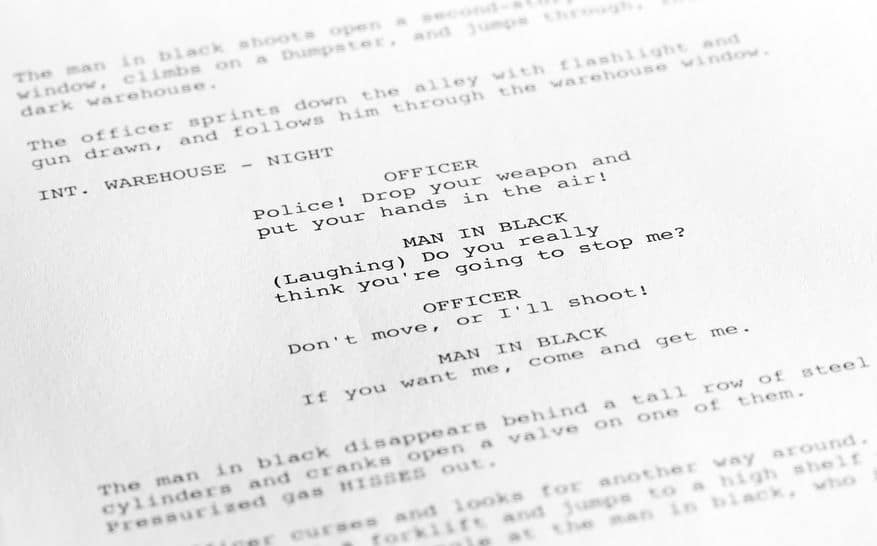

5. Write the Screenplay:

Format your screenplay properly using industry standards or screenwriting software like Final Draft, Celtx, Arc Studio, or WriterDuet.

Here’s a guide to excellent free scriptwriting software.

Remember, show, don’t tell. Visual storytelling is key in film.

6. Edit and Revise:

Review your screenplay for clarity, pacing, and relevance of each scene.

Trim unnecessary dialogue or action that doesn’t serve the story.

Get feedback from others and be open to constructive criticism.

Rewrite and polish your script until it’s as tight and compelling as possible.

7. Table Read:

Organize a table read with actors or friends to hear your screenplay aloud.

Take notes on what works and what doesn’t, and adjust accordingly.

8. Preparing for Production:

Once your screenplay is completed, begin planning for production by creating a shot list, securing locations, casting actors, and assembling a crew.

Here’s a guide to location scouting.

9. Be Flexible:

Be prepared to make changes during production as practical considerations arise.

Remember, the key to a successful short film screenplay is telling a compelling, complete story within a brief amount of time, so every element needs to be carefully considered, and each moment should contribute to the overall narrative.

You might also enjoy these five pro tips for getting your film selected for film festivals.

Closing Thoughts: Why Write Short Films Instead of Features?

Feature films are expensive to produce, and while writing scripts costs nothing, selling original feature scripts is tough.

Short films, on the other hand, are more accessible to produce than ever and an excellent medium for honing your filmmaking skills.

Focusing on a single character’s pivotal decision can create a compelling character arc within a short format, avoiding overly complex plots.

A well-crafted short film showcasing a character’s critical choice can act as a proof of concept for a feature or as a portfolio piece to pitch oneself as a writer or director for various projects.

Famous producers like Wes Anderson still create numerous short films in between his features.

Distributing short films is easy with platforms like YouTube and Vimeo.

Thus, creating short films is a strategic way to showcase your talent and potential for writing and directing larger projects in the evolving media landscape.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also like How Do Short Films Make Money?