Published: October 16, 2020 | Last Updated: December 5, 2024

The Hollywood Model Definition & Meaning

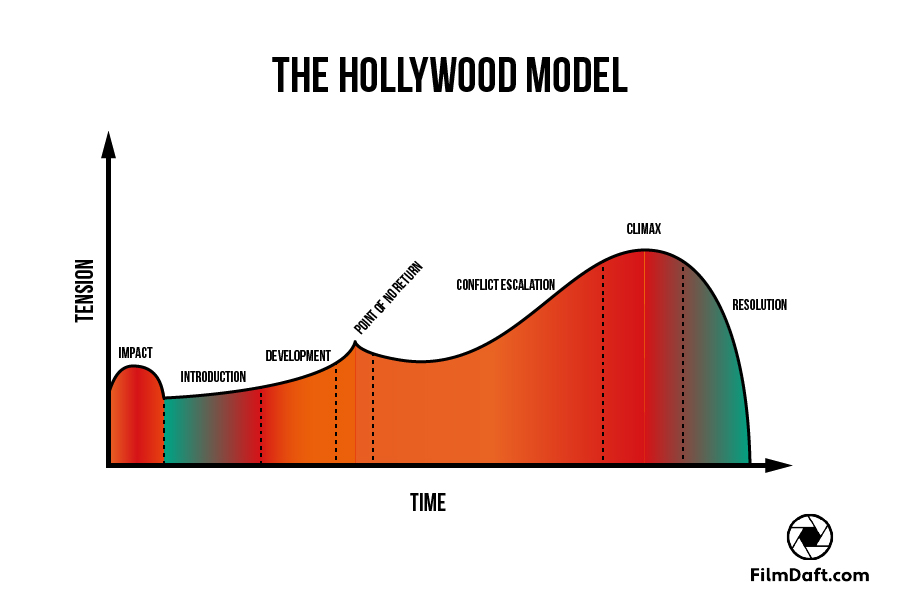

The Hollywood Model (aka the “narrative model” or “plot model”) describes how a film’s journey builds suspense and tension throughout the story. Originating from Danish media studies as “berettermodellen,” it outlines a typical narrative progression with six key stages:

The model is helpful when analyzing the structure of a film’s narrative, identifying key turning points, and understanding how the story engages the audience by managing tension and pacing.

The beats of The Hollywood Model with examples.

Before we discuss why a writer might choose The Hollywood Model over other story structure systems, let’s break down the individual beats of the diagram above with examples from familiar films to hone in on what makes this model unique.

See also Save The Cat regarding story beats.

Beat 1: The initial impact.

Every traditional story begins with a character living in a normal world. As writers, we learn early that beginning every story with the main character waking up is far from the most original way to begin a story.

The Impact beat of The Hollywood Model is a brilliant way to shake yourself out of the mindsight that your story has to start in a “normal way” just because your story’s protagonist begins their journey in a normal world. The idea is to intrigue the audience immediately while hinting at the tone and themes present in what’s to come.

Think about how some films start in the middle of the action, then go back and explain what’s happening later – like how we meet Indiana Jones during a temple raid in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

.jpg?bwg=1547379888)

Other films, like Goodfellas, The Departed, Wolf of Wall Street, or any Martin Scorsese movie, begin with a flashback and then explain it later.

.jpg?bwg=1547219031)

If you tell a non-linear story, you can combine both, as Quentin Tarantino does in Inglorious Basterds and Kill Bill Vol. 1, respectively.

.jpg?bwg=1547225040)

In both, we open on a flashback that we enter in the middle of with minimal exposition.

As we watch the scene and sequence play out, we are immediately gripped before jumping forwards or backward in time to learn more about the narrative consequences of the initial “impact” we just experienced through the following beat: the introduction.

Beat 2: The introduction.

The introduction is when the story orients us into the “normal” world of the story. After an exciting first sequence that hooks us in, the introduction presents everything we need to know: the time, the place, the characters, and the stakes.

It’s essentially the ‘who,’ ‘what,’ ‘where,’ ‘when,’ and ‘why’ of the storytelling necessary to get the audience on board with the rest of the film. While an introduction is self-explanatory, I like to point out how the more creative you are with this beat, the better.

Think about the wacky way Wes Anderson introduces us to the eccentric character of Max and the world he inhabits in the film Rushmore through a series of whimsical silhouettes:

.jpg?bwg=1547382704)

We learn that Max loves everything about his school except the actual school part, which is now a conflict for him if he wishes to remain at Rushmore. Beyond the introduction, The Hollywood Model suggests it’s time for development.

Beat 3: The development.

Development is where you flesh out the character’s world, and we learn more about their aspirations, fears, and relationships with other characters.

We also begin to understand how the conflict from the initial impact is created or continued. This is where other story structure models suggest throwing in an inciting incident and call to adventure.

This still of Ron Stallworth and Flip Zimmerman connecting and hatching their plan from Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansan is most indicative of this moment.

Things heat up as we head to the…

Beat 4: The point of no return.

The point of no return is when the tension rises to the point where conflict is inevitable. The story’s central tension has taken off, and our protagonists must continue. They are then thrust forward into action, creating rising suspense that drives the story to a point where they cannot turn back.

There’s no better example of this than when Marty McFly gets trapped in the future in Back to the Future. He’s in the new world now, and the tension becomes clear: He has to escape without ruining his future by messing up the past.

.jpg?bwg=1547147598)

Now, it’s time to escalate the conflict!

Beat 5: The conflict escalation.

We are now locked into the story’s central conflict, so this story beat is all about how the story continues to escalate tensions toward the inevitable conclusion.

The stakes should always get higher in the conflict escalation stage. Since this is The Hollywood Model, this beat in the story takes up most of the screen time.

No movie genre does this sequence better than the action movie. However, I like how the Rocky sequel/spin-off Creed plays with this sequence to build the dramatic stakes of the relationship between Adonis and Rocky, mirroring the rising stakes of Adonis’ fights.

As you can see, your protagonist must be put through the wringer. They’ve got to overcome challenge after challenge, each one more impossible to overcome than the last, increasing the audience’s suspense about whether or not they can reach their goals while building towards the climax.

Beat 6: The climax.

The climax of the film is pretty self-explanatory. In The Hollywood Model, it’s when the central tension is finally resolved. The climax of your story should feel inevitable. No matter what the protagonist does, this moment is destined to occur because every step along the way escalates it to this point.

Every film genre has specific conventions regarding the climax unique to their genre, but none are as consistent as the horror genre.

Inevitably, the thing the protagonist has been running from the whole film must finally be faced, and the best horror movies know how to tie the ghost, ghoul, or goblin haunting them to the main character’s central flaw.

The Babadook, written and directed by Jennifer Kent, demonstrates this via a terrific climax that ties “facing the monster” to the central theme of the whole film. You’ll have to watch it to get it 😉

The final Beat 7: The Resolution.

Once the story’s central tension is resolved, it is essentially over, except for an outro that resolves it and brings the film’s world back to normal.

In essence, the resolution is the come-down after the tension is relieved. The best resolutions guide the audience to reflect on what they’ve just seen vicariously as the characters from the story do the same. Sometimes, not much is left to be said after the climax, so resolutions can be as brief or as long as you feel they need to be.

Remember: once the central dramatic tension has been resolved, the audience is ready for the story to end, so don’t overstay your welcome.

.jpg?bwg=1547203711)

Source: Casablanca on Film-Grab.

Final thought: Why use The Hollywood Model?

You may wonder why you should use this storytelling model instead of the others we’ve shared on this site over the years. The reason is simple: this storytelling model gives you more flexibility to think outside the confines of Hero’s Journey.

“Berettermodellen” captures the perpetual motion of big Hollywood films better than the traditional three-act story arc model, which is more aligned with following every beat of Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” and can leave some Hollywood films feeling formulaic.

While the Hero’s Journey is a great resource to help structure your stories, many writers feel too restricted by its rigid nature. You can play with the story’s beats by thinking of your stories as continuous rising action. You don’t have to be restricted by refusals of calls, midpoints, or nonsense. Those story beats will occur naturally as you write anyway, but they can hinder creativity when you feel you must write to a specific set of rules.

The Hollywood Model lets you break from the more restrictive structure rules to be more free-form and loose. If you build your story’s central tension toward an inevitable confrontation, you can play with timelines and structure.

Next time you write, try thinking of your writing using The Hollywood Model and see if it helps you break from the more rigid structural systems you’re used to.

Read Next: What is the Actantial Model?

HI Grant, thx for this content of using the Hollywood model. I am student of The Dutch Filmers Academy in the The Netherlands. I am writing my thesis about Tracking shots. Now i am looking for a model to use this to analyse 25 selected trackings shots. The goal of my thesis is to use a objective model to score and rank these 25 differents hots to finally present the “most execellent trackigs hot ever made. Could you maybe point me to some content of a model to use to analyse and score these shots. There are lost of rankings of trackings shots but nobody is telling how they selected these (all more or less personal views..)

Many thanks in advance N. Bruinier 12 -12 2021

Hi Noud,

So you are saying that you want a definitive ranking formula that can be applied to determine whether one tracking shot is actually better than the other. While I’m certainly not the most qualified to answer this, I can help give you some ideas on what to look out for based on what qualities usually make film critics and filmmakers rave about a new tracking shot from this movie or that TV show:

1. Duration – the length of the shot usually sets a huge milestone. For instance, the length of Alfonso Cuaran’s tracking shots in Children of Men won a ton of accolades at the time and were heralded as groundbreaking based on their length alone. Then when the film Birdman came out, the whole film was conceived as “one continuous take” which won it a lot of praise, though I think technically it was shielded by clever cuts and was actually filmed over multiple takes. I believe this was also the case for 1917, but I don’t know which one has more cuts. Which brings me to the second data point:

2. Number of cuts – if, for instance, a tracking shot does have cuts, then that would lower its rank. So if a film is “one tracking shot” but with multiple cuts, it would have to be ranked lower based on the actual duration of each shot. If you were to compare Birdman to Children of Men, you would then need to take the longest tracking shot from each and compare them based on length. Interestingly, the film Victoria was actually shot in three continuous takes (I believe they may have cut between the three, but still) so that film could actually rank at the top if based on number of cuts / duration alone.

3. Movement / distance – for a tracking shot to be “tracking” it needs to be in motion. The next metric would need to be some way to quantify how much “movement” the shot follows. For instance, it could be hard to quantify what makes the tracking shot following Clive Owen’s character in Children of Men stronger than the tracking shot that opens Boogie Nights outside of how long it is. But if you could actually record how much distance the characters walk in terms of steps or kilometers / meters, then you would have some way to account for the actual distance covered, which could be another way to rank each shot.

4. Scale – now, this one is the second hardest to measure in terms of a quantifiable ranking, but it also should be taken into account. Think of the action sequences in 1917 or Children of Men and compare them to the shots in Victoria or Birdman. Clearly the latter two are more impressive in terms of the scale of production that was required to pull of each shot. That’s not to say that the other shots chasing Michael Keaton around the theater or Laia Costa around Berlin weren’t impressive or complex in their own right. But pulling off action sequences with hundreds if not thousands of moving parts between cast members, intricate set design, and perfectly timed explosives is an incredible feat and should be included in whatever ranking formula you come up with.

I struggle with this one because you could technically use the production budget as a quantifiable metric, but then that would tip the scale in favor of larger productions, so I don’t think that’s fair. You could also use the hours of prep / rehearsal required to measure “scale”, but that also doesn’t feel quite right. Perhaps the best way to measure this would be some combination of the two plus a simple “wow factor” ranking where you screen the shots in front of a series of neutral audiences and poll them on how impressed they were. In order to keep this fair, you would want to have a different audience of the sample size watch each shot that you are ranking so they don’t compare the shots between each other.

For instance, if you were going to show the same audience 1917 and then Victoria, they would naturally rank Victoria lower in comparison to 1917. But if you showed one audience Victoria and one audience 1917, then you could gauge how impressive each shot is based on its own merits. Maybe this isn’t the perfect way to do this, but just an idea.

5. Framing / artistry – this is the metric I will be the least helpful with, as I think this is something that true cinematographers will be able to gauge far better than myself. Perhaps the solution to this metric is to poll a sample size of cinematographers and have them rank the quality of the framing of each shot based on a few core cinematography rules.

For instance, any old tracking shot can show a lot of movement and cover a lot of distance for a long period of time – but how many can keep the main subject in frame the entire time, while also keeping them lit in a way that’s tied to the emotions of the scene, all while the actor gives a performance that is emotionally true, and still show off all the action happening around the character?

Which brings me to the last metrics…

6. Performance – in order to rank if a tracking shot is truly worthy, the performances of the actors have to still resonate with an audience. Its one thing to follow the actor through a perilous journey across vast distances with scale and perfect framing, but is the performance hindered by the cameras rolling so long? In a way, a “one shot” tracking shot leaves the actors completely on their own. The scene will live or die by a single performance. Not only do they have to worry about hitting all their marks and timing on a technical level, they also have to be fully in the moment, because if the performance isn’t there, who cares if the shot is a one-take? By default, the tracking shots that make it into the film must have strong performances, but the longer the shot gets, the harder it is for the performance to remain dialed in the entire time. Could there be a great shot where the actor loses steam halfway through before gaining momentum and getting it back by the end? If so, this could lower its rank, and put it below another, shorter or less technically-complex shot. Film is, after all, a medium for emotional storytelling, and actors are the vessels through which the audience experiences the emotions of the story. If we disconnect from them, a shot can be as impressive as it wants – but it won’t make a great story.

Okay, so those are my ideas! Now how you formulate these into a ranking system is anyone’s guess. For the purpose of your thesis, I would probably give each metric a weight to it based on what you personally value. For instance, if you value the technical aspects more than the theatrical, then by all means, weight them higher. If you value the artistry more than a shot’s length, then definitely weight the framing and performance higher than duration or distance covered. It’s up to you from here, but hopefully this helps you organize your own thoughts to decide what you agree with and what you don’t. If you have any other questions, feel free to reach out.