Screenwriting features a variety of structural approaches that help writers organize their narratives.

Below are some of the most common screenwriting methods, each designed to guide the storytelling process uniquely.

Table of Contents

1. Save The Cat Beat Sheet

Developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder, the “Save the Cat” beat sheet breaks down film narratives into 15 distinct “beats” or plot points.

This structure ensures that the screenplay has a solid and engaging arc, focusing on the transformation of its characters. It emphasizes the importance of making the protagonist likable early on (hence the name “Save the Cat”).

The Save the Cat Story Beat Sheet

- Opening Image: A visual representing the tone, mood, and type of story we’re about to watch.

- Theme Stated: The theme or message of the story is stated, often subtly, to set up what the protagonist will learn.

- Set-Up: Introduction of the protagonist’s world before the adventure starts, including the protagonist’s life, flaws, and environment.

- Catalyst: The inciting incident that shakes up the protagonist’s world and sets them on the story’s path.

- Debate: The protagonist’s hesitation or questioning of the journey ahead. It’s a moment of doubt before committing to the adventure.

- Break into Two: The protagonist makes a choice, and the story shifts into a new, often contrasting, direction as Act Two begins.

- B Story: A subplot, often involving a love interest or secondary theme, that complements and enriches the main storyline.

- Fun and Games: This is where the premise’s promise is delivered, showing the protagonist engaging with the new world and its challenges.

- Midpoint: A pivotal moment that changes the game, often elevating the stakes and shifting the story’s direction.

- Bad Guys Close In: External and internal pressures mount on the protagonist, complications abound, and everything worsens.

- All Is Lost: The lowest point for the protagonist, where failure seems inevitable, often featuring a symbolic or actual “death.”

- Dark Night of the Soul: The protagonist’s moment of greatest vulnerability and doubt, pondering over what has been lost and how to proceed.

- Break into Three: Having gained new insight or received help, the protagonist finds a way to approach the problem anew as Act Three begins.

- Finale: The climax where the lessons learned are applied, conflicts are resolved, and the protagonist emerges transformed.

- Final Image: A mirror of the opening image, showing how the protagonist and their world have changed due to the journey.

Example: “The Lego Movie” – This film follows the Save the Cat structure closely, with clear beats such as the opening image, the theme stated, and the night of the soul before reaching its resolution.

Read more about this story beat sheet in Save The Cat! Beat Sheet Explained. What It Is, And How To Use It.

2. Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey, or Monomyth, was articulated by Joseph Campbell. It outlines a broad, universal narrative structure many myths from different cultures follow.

The journey includes the Call to Adventure, the Encounter with the Mentor, Crossing the Threshold, the Road of Trials, the Return, and many others.

Example: “Star Wars: A New Hope” – Luke Skywalker’s journey from a farm boy to a hero who helps destroy the Death Star closely mirrors the Hero’s Journey structure, featuring almost all its stages.

Read more about The Hero’s Journey in Campbell’s Monomyth: A Guide To The Heros Journey

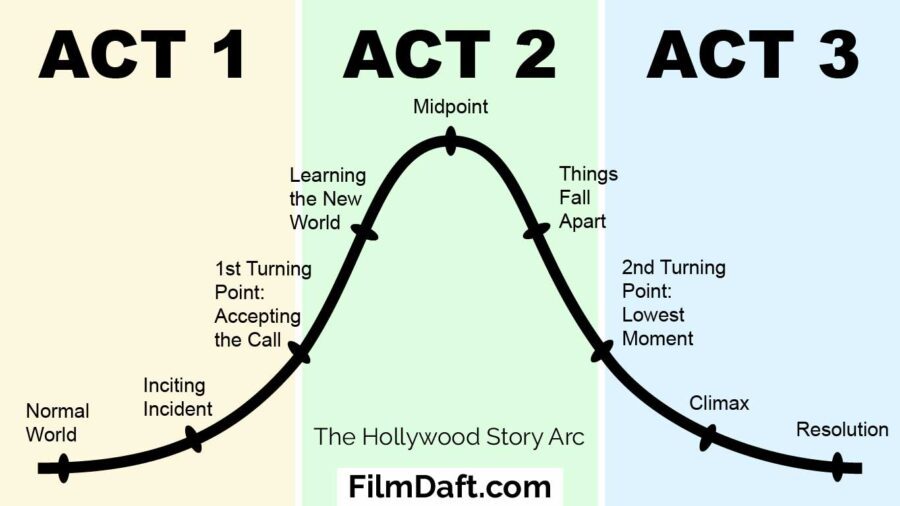

3. 3-Act Structure

Perhaps the most classic narrative structure, the 3-act Structure, divides the story into three parts: the Setup (introducing characters and the conflict), the Confrontation (with rising action and complications), and the Resolution (where conflicts are resolved).

This structure is highly versatile and can be adapted to various stories.

Read more about narrative and story structures.

Example: “The Godfather” – The film is a prime example of the 3-Act Structure, with the setup involving Vito Corleone’s daughter’s wedding, the confrontation following Michael Corleone’s deeper involvement in family affairs, and the resolution showcasing his rise to power.

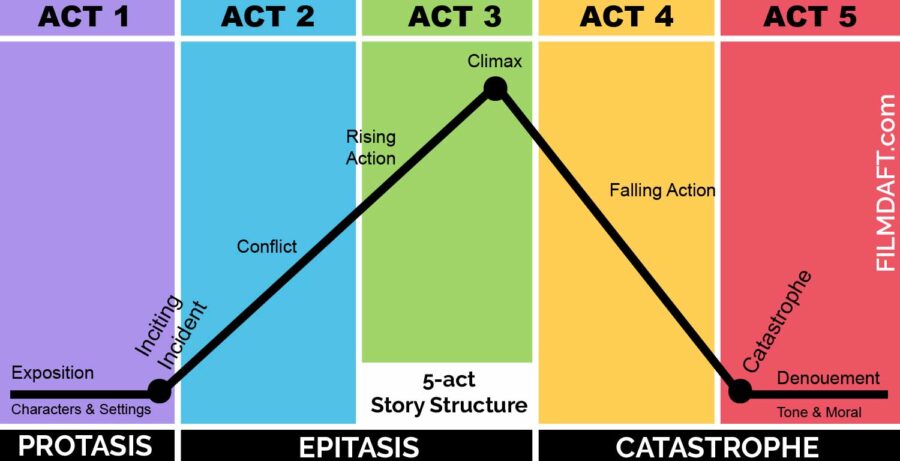

4. 5-Act Structure

Originating from classical drama, the 5-act Structure offers a more detailed division of narrative progression: Exposition (prologue/introduction), Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Denouement. This structure allows for a more nuanced development of plot and character.

Example: “Hamlet” (Though not a movie originally, many film adaptations follow this structure) – Shakespeare’s play, and its adaptations, follow this structure, with Hamlet learning of his father’s murder, plotting revenge, facing the climax in the confrontation with Claudius, and the eventual tragic resolution.

5. Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Inspired by the Hero’s Journey, Dan Harmon’s Story Circle is an eight-point narrative structure focusing on the psychological journey of the characters.

It starts with a character in a zone of comfort. They want something, enter an unfamiliar situation, adapt to it, get what they want, pay a heavy price, and then return to their familiar situation, having changed.

Example: “Rick and Morty” – As one of Harmon’s creations, many episodes follow this structure closely, with Rick and Morty experiencing personal change through their interdimensional adventures.

See more in The Dan Harmon Story Circle Explained

5. The Sequence Approach

The Sequence Approach divides the screenplay into smaller, manageable sequences, each with its mini-arc, and the Mini-Movie Method expands on the Sequence Approach by treating each act of a screenplay as a standalone “mini-movie.”

Example: “Pulp Fiction” – “Pulp Fiction” exemplifies the sequence approach to screenwriting by structuring its narrative through interconnected, episodic sequences. Each sequence is a mini-story within the larger plot, allowing for nonlinear storytelling and character development across diverse yet intertwined vignettes.

Conclusion

In screenwriting, various approaches like the Save the Cat Beat Sheet, Hero’s Journey, 3-Act Structure, 5-Act Structure, and Dan Harmon’s Story Circle offer unique frameworks for storytelling.

Each method provides a roadmap for plot development and character arc, catering to different narrative styles and genres.

These approaches guide writers in crafting compelling, well-structured stories that engage audiences.

Up Next: What is the Climax in a screenplay?