DISCLOSURE: AS AN AMAZON ASSOCIATE I EARN FROM QUALIFYING PURCHASES. READ THE FULL DISCLOSURE FOR MORE INFO. ALL AFFILIATE LINKS ARE MARKED #ad

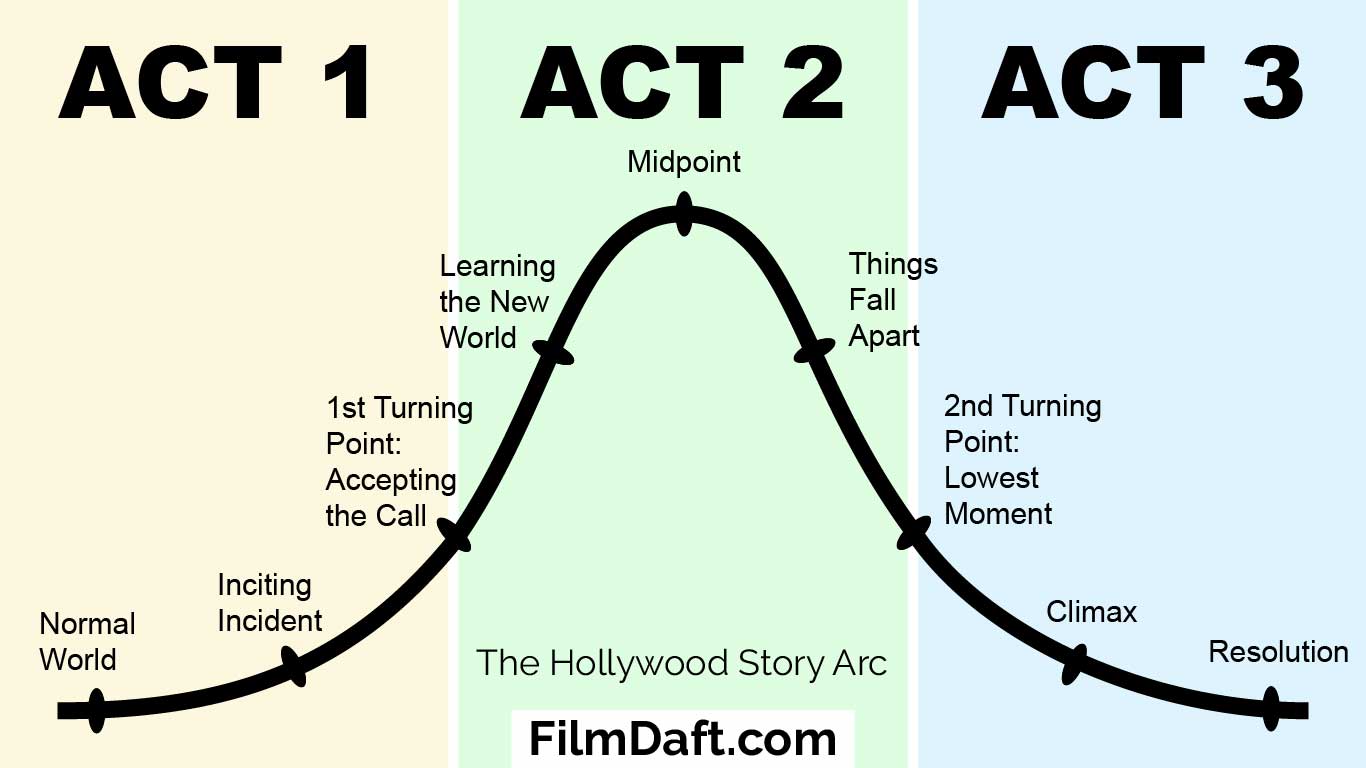

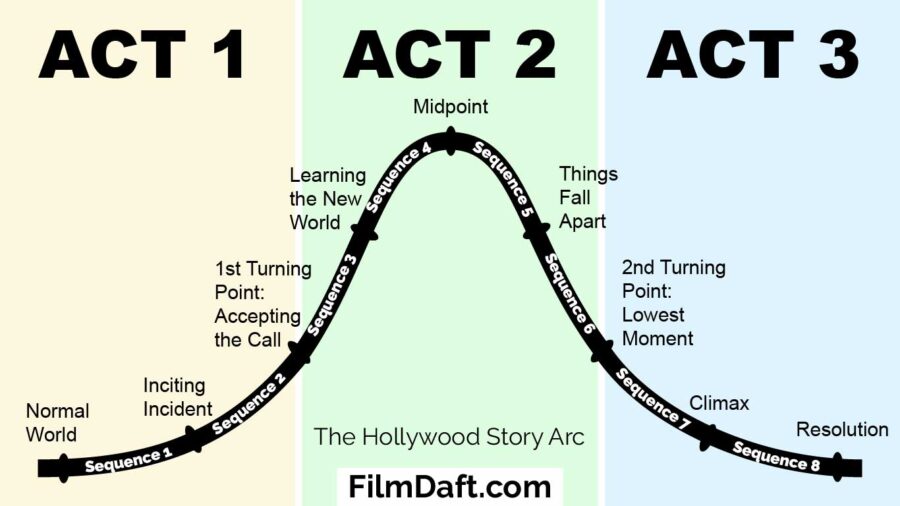

Definition: The Hollywood Story Arc is a classic or three-act structure used in narrative fiction. The model divides a story into three parts: the setup, the confrontation, and the resolution. This structure is widely used in film, television, and literature, particularly in Hollywood cinema, hence the name.

In this article, I’ll first briefly review each element of the Hollywood Story Arc.

Then, I’ll give some examples of each element from famous movies.

Table of Contents

The Hollywood Story Arc: The Three Acts and their Eight Elements

The origin of all modern film storytelling can be traced back to the popularity of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero of a Thousand Faces (1949).

The Hollywood Story Arc is no different and similar to the hero’s journey.

Here’s a breakdown of each act:

Act One: The Setup

- Normal World: Introduction to the main characters, their world, and the status quo.

- Presentation of the central conflict or problem the protagonist must face.

- Inciting incident: An event disrupts the balance and propels the protagonist into a new situation or journey.

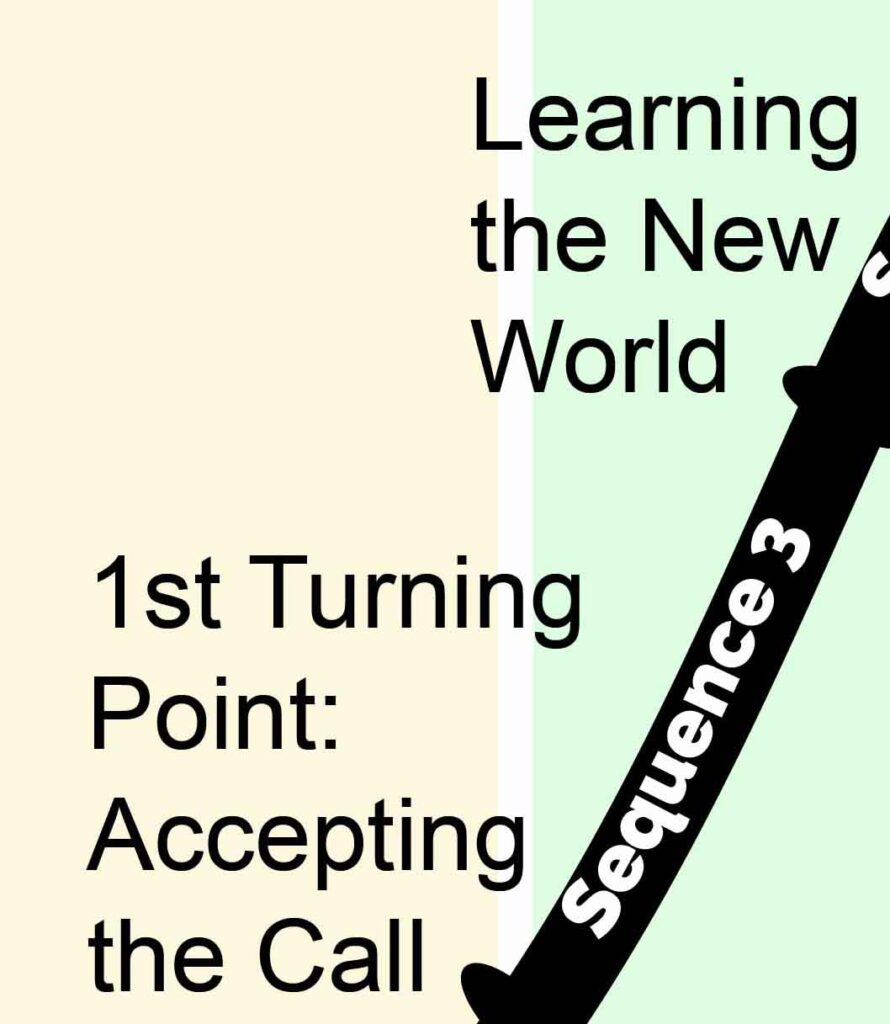

- 1st Turning Point: The first act ends with a “plot point” or “turning point” that fully engages the protagonist in the conflict and sets the story into full motion.

Act Two: The Confrontation

- Learning New World: The protagonist faces obstacles and challenges that test their resolve and force them to adapt to the new status quo and grow.

- Also known as “rising action.”

- Development of subplots, secondary characters, and further complications.

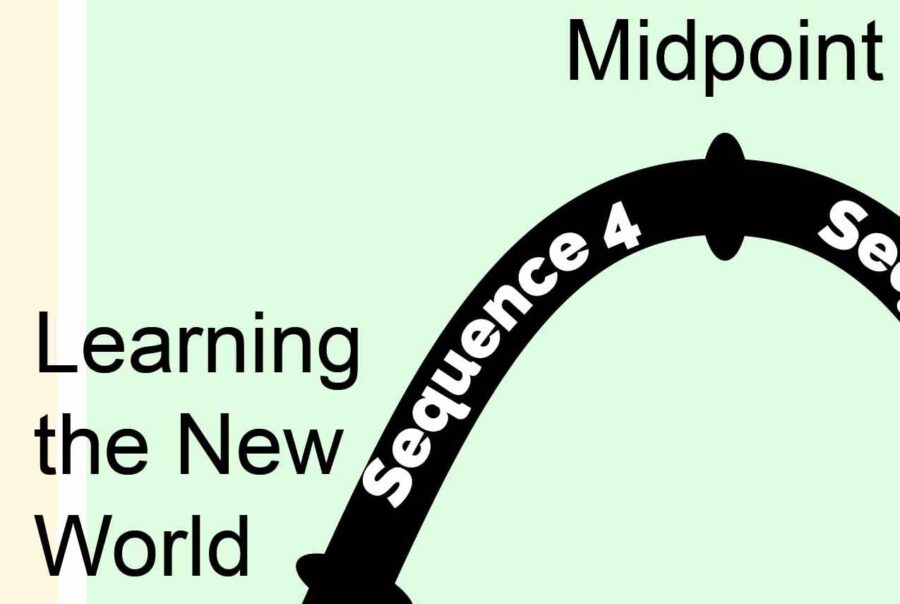

- Midpoint: The stakes are raised, and the story’s direction may take a significant turn. It seems like the protagonist has gotten what they set out for, or at least, a version of it. But they’re not done yet.

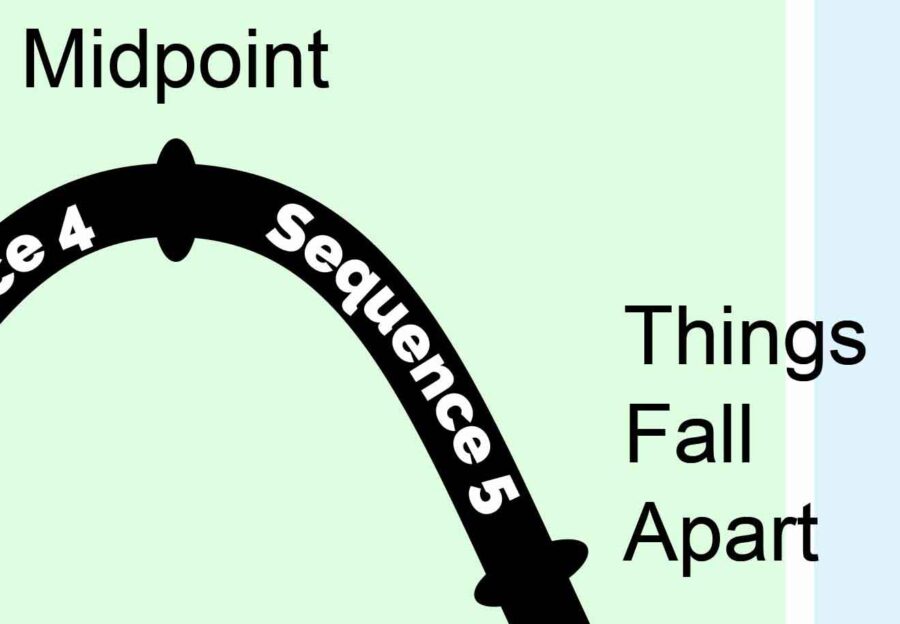

- Things Fall Apart: Things turn ugly after that high midpoint. This fall leads the protagonist to their darkest despair.

Act Three: The Resolution

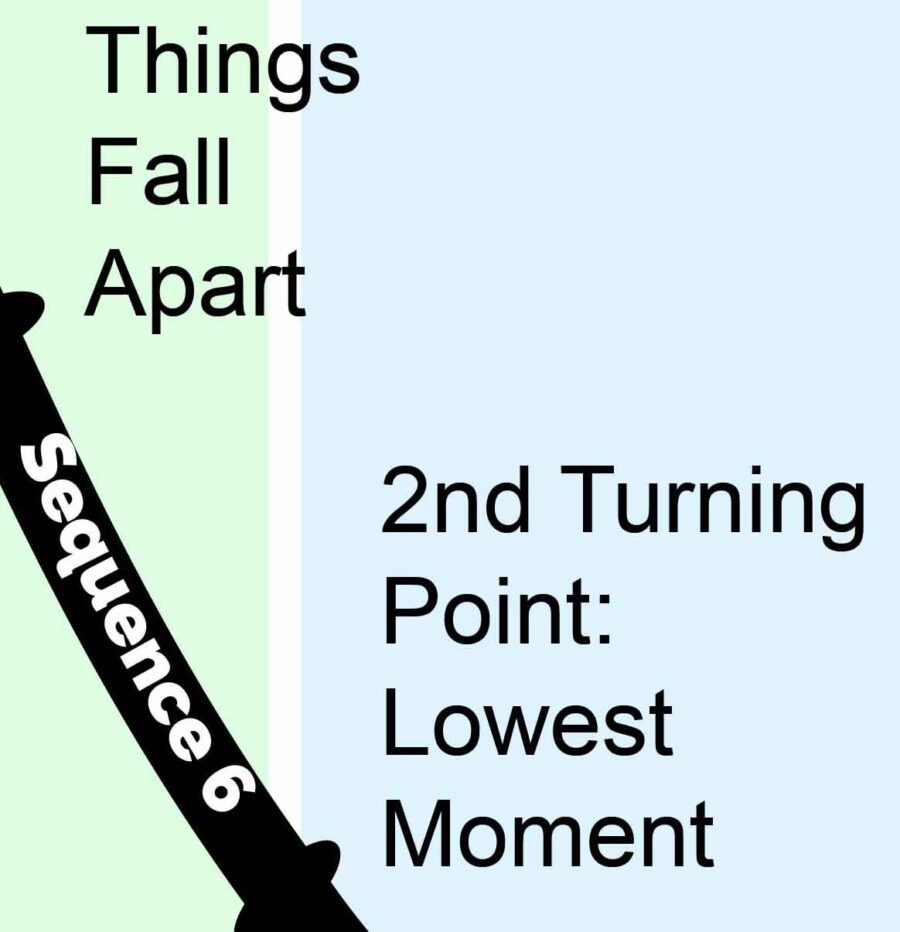

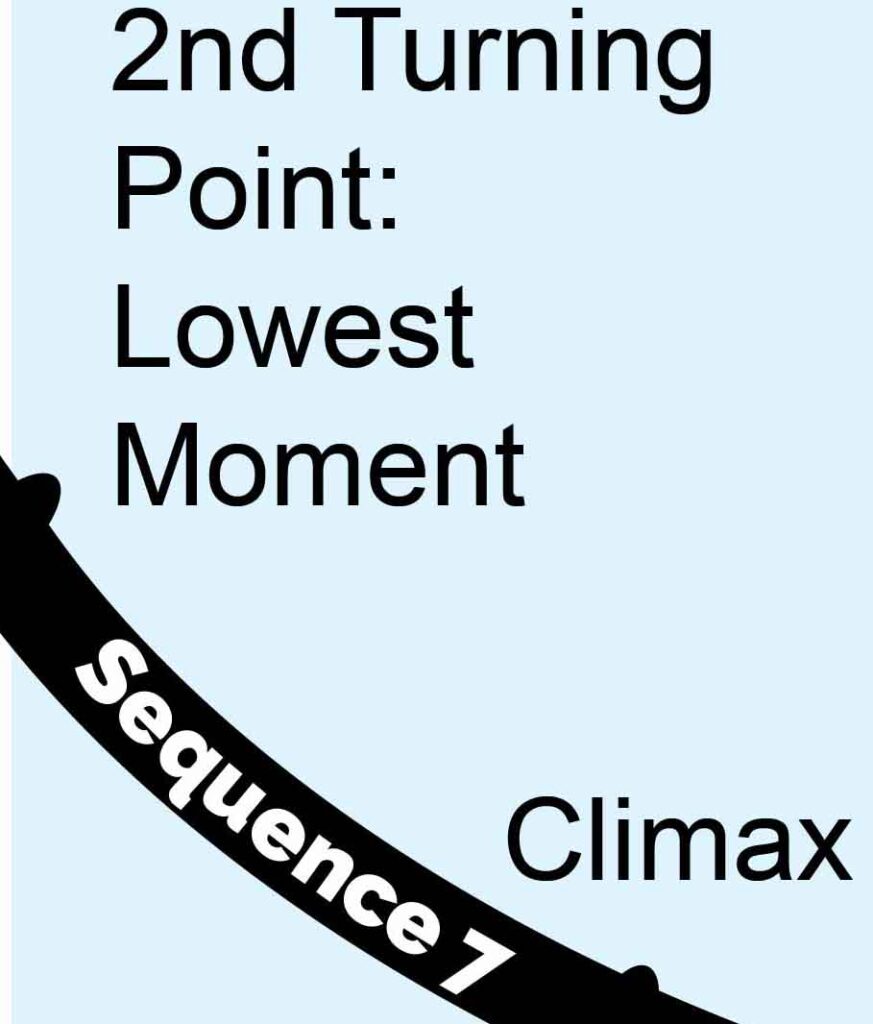

- 2nd Turning Point: The protagonist faces their lowest moment as we transition to the last act.

- This is also the setting up of the climax.

- Climax: The story’s climax is where the protagonist confronts the primary conflict. It’s the highest point of tension, where the outcome is uncertain. Read more on Climax in movies here.

- Resolution: The story concludes with an outcome or resolution where a new (better/worse) status quo is established, and the story’s loose ends (subplots and secondary conflicts) are tied up.

Famous Movie Examples of The Eight Narrative Points of the Hollywood Story Arc

Each notch on the Hollywood Story Arc represents a different story beat.

Below, I’ve divided the time between each beat into eight sequences using examples from famous films you should recognize.

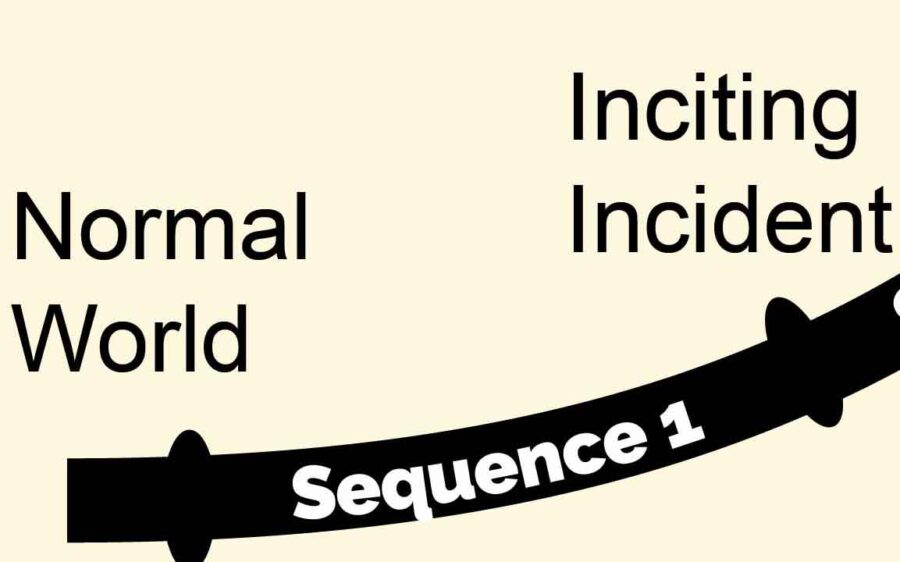

Sequence 1: Establish the normal world.

For every good story to begin, there has to be a normal world as a starting point for our character to venture out from.

The “status” must start off as “quo.”

We need a normal world for three reasons:

- to present the central conflict

- so that something interesting can happen

- so that we get to know our hero

Think about the character of Luke Skywalker in Star Wars.

.jpg?bwg=1547407615)

Luke’s life on Tatooine is Luke’s normal world, boring him to death.

At one point, Luke tells R2D2, “If there’s a bright center to the universe, you’re on the planet it’s farthest from.”

.jpg?bwg=1547407615)

This is a great starting point for Luke and shows his inner frustration and conflict between being loyal to his uncle and aunt and his longing for adventure.

The movie’s opening, where Darth Vader lands on Princess Leia’s ship, establishes the great conflict between the evil Empire and the good Rebellion in the galaxy.

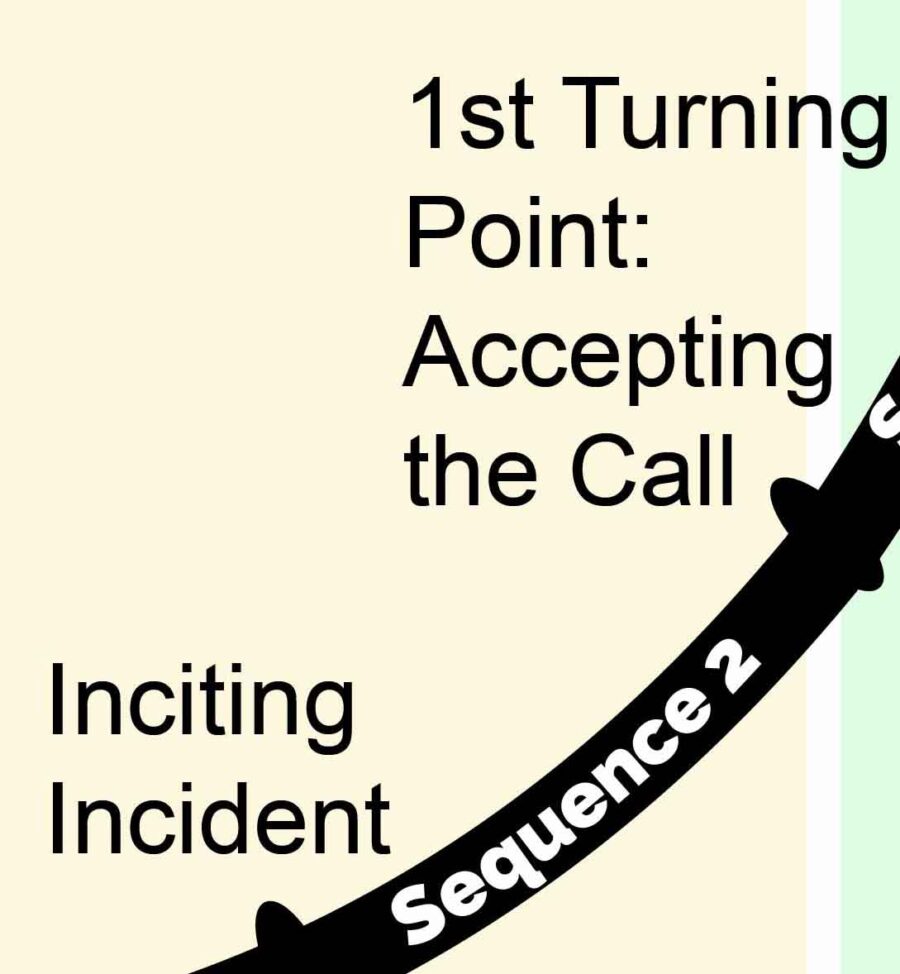

Sequence 2: The Inciting Incident occurs.

The inciting incident is the catalyst for everything that comes after.

It might not always be the big moment that changes everything for our character as they set forth on their journey, but it’s the spark that tells us something unusual will happen.

.jpg?bwg=1547407615)

In Star Wars, the inciting incident for Luke is when he discovers the hologram of Princess Leia that pops out of R2D2, informing Luke he needs to find Obi-Wan Kenobi.

Sequence 3: The first turning point.

In sequence 2, the character is thrust onto a path that leads them towards their first turning point.

This first turning point is a big character moment for your protagonist. It is their first time choosing the story outside their new world’s comfort zone.

It can be both a physical or a mental and emotional turning point.

By refusing and accepting the call, there is a genuine moment of character growth – the first step to overcoming their flaws, facing their fears, and going after their goal.

Think about the moment in Gladiator when Maximus is offered the opportunity to fight for his freedom and must choose to accept or deny it.

Sequence 4: Learning the new world.

After the call has been fully embraced, the characters then thrust themselves into the new world.

This process of learning the new world can look in many different ways, and learning the new world requires the help of a scholar-like figure to show our character the ropes.

Think Obi-Wan Kenobi explaining the Jedi and the force to Luke in A New Hope:

.jpg?bwg=1547407617)

Another part of learning and adjusting to the new world comes when the character faces their first real trials and tribulations.

In Batman Begins (2005), Bruce Wayne returns home at the beginning of Act 2 and starts setting the things he’ll need to become Batman in motion.

.jpg?bwg=1547148953)

.jpg?bwg=1547148952)

This is a common storyline for the first sequence in Act 2, particularly among superhero origin stories.

Training montage or not, keeping the story’s world expanding throughout this sequence is key to keeping the story feeling original and exciting as you reach.

For screenwriters, it’s a great sequence to have some fun with.

Sequence 5: The midpoint.

The midpoint is the false ending. It’s when your protagonist thinks they’ve made it, or there’s a light at the end of the table, and it all comes crashing down around them.

In the best-case scenario, the midpoint should mirror the film’s end. The characters should have a version of what they want, not what they need.

The midpoint complication

Sometimes, something complicates things even more when the hero thinks they’re out of the woods. This is called the midpoint complication.

For instance, in Saving Private Ryan, the team finds Ryan around the film’s midpoint – the only problem is he wants to stay and fight with his comrades.

Success can be its own enemy – or the enemy could get stronger just when you think you’ve escaped, like in Alien.

.jpg?bwg=1547142831)

When you construct your midpoint, think about how you are mirroring your ending or at least playing with the expectations of your ending.

In the case of Alien:

- Midpoint: Ripley (and crew) think she’s safe from the Xenomorph (what she wants).

- Ending: Ripley is safe from the Xenomorph (what she needs).

Sequence 6: Things fall apart.

This is the sequence when everything starts to go downhill for the lead.

They got what they wanted but not what they needed, and now they are paying the price for not solving their real issues.

In Saving Private Ryan, the heroes find Ryan (what they wanted), but he refuses to leave to be saved (what they needed).

As a result, they now find themself defending a destroyed town against an entire tank unit.

Similarly, in Star Wars, things also go from bad to worse.

Our heroes have just rescued Princess Leia and escaped from the Storm troopers through a quick and easy escape hatch.

There’s just one problem – the hatch is a trash compactor, and it’s trash day, baby!

.jpg?bwg=1547407615)

Sequence 7: The second turning point and the lowest moment.

As the characters continue their descent, the second turning point comes around.

The second turning point is what an early screenwriting professor at Santa Barbara City College named Jon O’Brien coined the “popeye” moment, where the character stops and says, “I’ve had all I can stand, and I can’t stand no more!”

.jpg?bwg=1547296447)

This lowest moment is like the night of the soul.

It’s rock bottom but also the necessary place for emotional change.

I’ve had all I can stand, and I can’t stand no more!

– Popeye

In The Dark Knight, Batman faces his lowest moment when The Joker makes him choose between rescuing his lover Rachel or the hero cop Harvey Dent.

.jpg?bwg=1547463350)

But it turns out he’s been tricked, and when he rescues Rachel, he finds Harvey waiting for him.

He’s left with nothing left of Rachel but ashes. A dark “knight” of the soul, if you will.

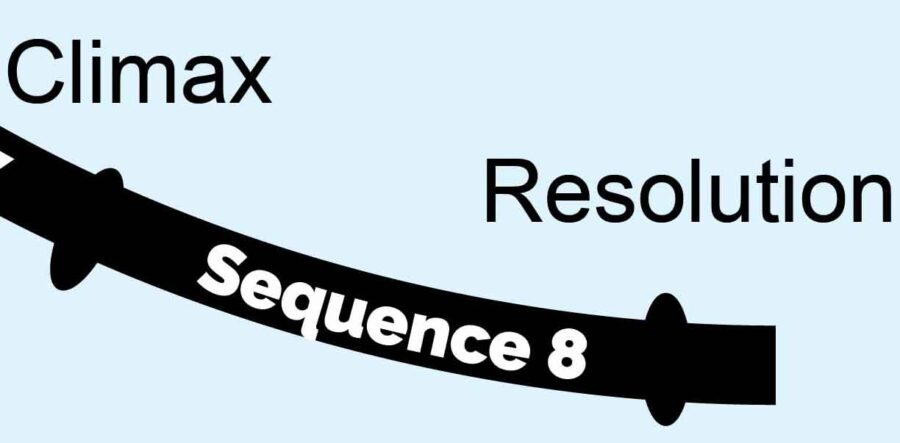

Sequence 8: The climax and resolution.

The climax is when the rising central conflict requires the main character to make a dramatic decision to get what they want.

The resolution is the conclusion, detailing the aftermath for the character after the cathartic events of the climax.

The climax can take anywhere from two minutes to ten, while a resolution can be a single scene or several, depending mainly on how much is left to be said about the characters and what they’ve learned at the end of their journey.

For instance, a film like The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly has a long and drawn-out climactic final battle – but the resolution is relatively short.

.jpg?bwg=1547465715)

After the results of the gunfight, our hero rides off into the sunset, like so…

.jpg?bwg=1547465715)

Your climaxes and resolutions are entirely up to you.

At this stage, when writing your movie script, I recommend you ask yourself these questions:

- Does your climax resolve the story’s central dramatic tension?

- Does your climax answer the central dramatic question you set out to ask?

If not, you may need a longer resolution to tie up loose ends and pay off all the elements you set up throughout the story.

At the end of the day, how you choose to resolve your story is entirely up to you.

Conclusion.

And that’s it! That’s all you need to know to follow the Hollywood storytelling model to tell your stories.

If you want to learn more about different structural tools you can use to outline your own stories using this model, check out this piece on How to write a story that works.

Otherwise, good luck with your writing, and reach out if you have any questions!