The general rule of thumb is that a screenplay written in the proper format is equivalent to one page per minute of screen time. Therefore, a screenplay for a two-hour movie will be 120 pages (2 hrs = 120 mins = 120 pages).

However, that’s just a rule of thumb. In reality, a movie’s length related to the screenplay varies depending on the type of film you’re writing and how you write it.

For example, there’s a big difference between writing “the two dudes get into a fight” and describing the whole fight sequence.

In this article, I’ll discuss exceptions to this rule, how the rule is closely related to the three-act structure, and how to use the rule and three-act structure to improve your writing pacing.

Table of Contents

Why is the one-page-per-minute rule important?

When delivering screenplays to studios and producers, especially as an unknown writer, this is a metric they will use to judge the film’s length.

This is true for television and shorts as well.

A half-hour TV pilot will be around 20-30 pages, and an hour of drama will generally be between 50-60 pages.

Read more about writing for TV or streaming giants like Netflix.

As mentioned, this rule has some exceptions, and certain types of films can alter this metric.

Additionally, there are some ways the relation of page-to-minute can help you pace your screenplay.

Film data researcher, educator, and screenwriter Stephen Follows has a great data set on the length of movie scripts.

Notable Exceptions to the One-Minute Rule

Some types of films mess up the page-to-minute rule.

The most common thing that changes this is films with plenty of action and a lack of dialogue.

Typically, you do not want to direct your writing. When writing action, many writers tend to get overly specific.

Unless the action is pertinent to the story, or if it’s a project you will be directing yourself, it’s better to suggest what will happen and move on.

Because of this, scripts that are heavy in action will read much shorter.

A single paragraph of action may take up to 5 to 10 minutes on screen but only be three lines (it’s good to try and keep your action paragraphs under three lines, but more on that later).

Examples of scripts that differ from the one-minute rule

An example is the script for the Battle of the Bastards-episode in ‘Game of Thrones.’

Though the episode is an hour long, the script is 41 pages long. For those of you who have watched, this episode is where action heavily outweighs dialogue.

Another example of a great script shorter than the movie’s length is Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation.

Since this film deals explicitly with a lack of conversation and features many meditative moments of silence, it isn’t surprising that the script is only 75 pages while the film is 1:44 minutes.

If you find an online PDF of the script, you will notice that many pages are doubled with plenty of blank space. This trick can help understand the pacing the film should take while reading.

Pacing

Understanding how your screenplay relates to timing on-screen can help you pace your film accordingly.

For the most part, the average scene in a film is one to three minutes long.

That may not sound very long, and you’re right. This means that it is essential to be concise and direct. See here how to write screenplay format.

Considering that, over film history, the average shot length and scene length have only been diminishing.

Many screenwriters want to start their scene from a character’s entrance. If this doesn’t contribute to the story, don’t write it!

If you submit to studios, know these people must read hundreds of scripts and are extremely critical.

This is also why keeping action paragraphs under three lines is a good idea.

Trust me, if you have plenty of scripts to read, seeing paragraphs of text will turn you off.

Keeping it short lets the story move quickly and often makes for an easier read.

Scenes vs sequences

A collection of scenes that encapsulate an event is called a sequence.

For the most part, a sequence will consist of three to five scenes (of course, remember these numbers are all suggestions).

That means your default sequence will be 10-15 pages or 10-15 minutes.

See a page breakdown of Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat! Beat Sheet here.

Always make sure your sequence is understandable!

Whether it’s a linear course of action or cuts between two parallel scenes, it needs to be logical and understandable.

Too much jumping around too quickly is disorienting and should be avoided unless intentional.

Sequences vs acts

It is also important to remember that you will want your sequences to fit into your different acts.

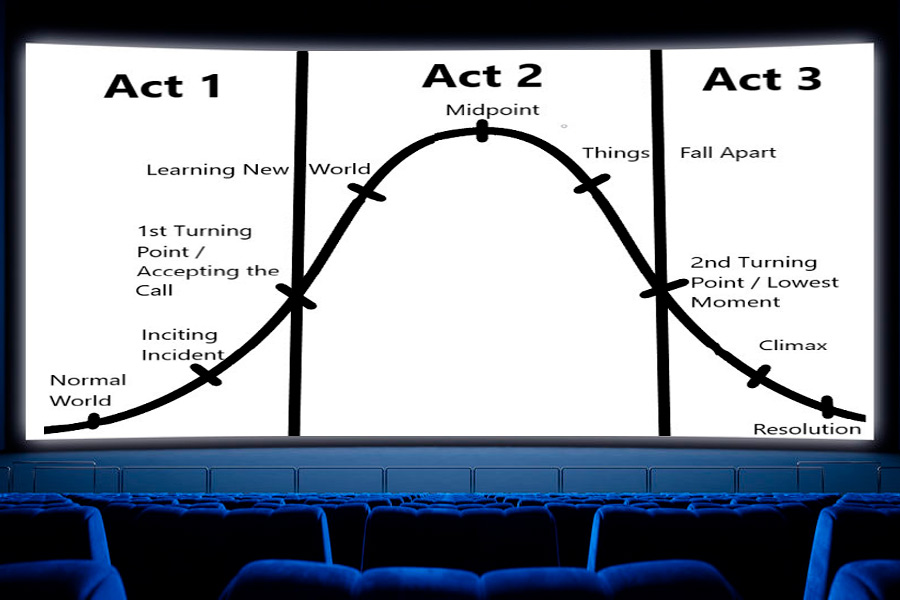

Chances are you’ve heard about the three-act structure, so I won’t go too much into it except how it relates to a film’s page length and pacing.

Pretty much every film consists of three acts.

In a two-hour film, the first act tends to be 30 pages, the second around 60, and the third act around 30 pages.

This means the first act break is around 30 minutes in screen time, and the second act break will be close to minute 90 for a two-hour film.

Watching movies while thinking about this can help you spot how these transitions are handled.

This standard type of pacing is also what makes it very difficult to write the first act.

In the first 30 pages (for a typical film), you must introduce the main characters, their origin, the inciting incident, and the story’s conflict.

Packing this into 30 pages means you can’t dwell too much on extraneous detail.

Big moments of action, fun scenes, and big set pieces are better reserved for the second act.

I also recommend this article on Dan Harmon’s Story Circle.

Keep things moving in the first act.

It’s also good to keep things moving in the first act because it is rare for a producer or someone taking unsolicited submissions to read past page 20!

Unfortunately, if you are an unknown writer, you cannot wait until the script’s end to convince anyone.

A strong first act is the most important thing to get someone to read through your script.

Coming up with a strong opening scene and interesting ways to introduce characters and the conflict is essential.

To do this, think about how to pace your writing. If possible, try to keep your action paragraphs short and your scenes under three pages.

Tie your scenes together into sequences, vary moments of action with moments of dialogue/exposition, and alter between emotional highs and emotional lows.

Keep the end product in the back of your head at all times

Make sure the story you are telling fits the format you’re writing in.

You will write unnecessary pages if you have trouble with length and need to fill space.

Instead of doing this, think about why you don’t have enough (or too much) material to write about and the type of story you’re writing.

Perhaps it should be a TV show instead of a movie, or vice versa?

A super helpful way to think about this that I picked up from a Story Editor at WME is that a movie is (generally) an interesting event in a normal person’s life, and a TV show is the normal life of an interesting person.

a movie is an interesting event in a normal person’s life and a TV show is the normal life of an interesting person.

All that to say, if you pay attention to the page length and the length of your scenes, you can vary the pacing and juxtapose moments of action with moments of dialogue to create a dynamic and interesting read.

Conclusion

There are no rules to screenwriting, and these suggestions are simply tools to help guide you in moments of uncertainty.

The most important thing is to have a solid and engaging story, which can take many forms.

Personally, the biggest thing I like to consider is the reason I have for making the film and who the audience is.

The three-act structure and quick pacing are essential if you’re trying to make something commercially viable and get some money behind your film.

If your film will exist outside of the studio system, more personal, or that you intend to make on your own, the way you write it should be for yourself.

Unfortunately, these two worlds rarely combine, so knowing your ultimate goal is helpful.

See how long it takes to write a screenplay for a movie.

I hope that these guidelines helped. As someone who has read for screenplay competitions and studios, I guarantee you that receiving a script that reads quickly and easily is a relief and always appreciated.

That doesn’t mean your script can’t be intellectual or tackle complex subjects.

Still, I strongly suggest against paragraphs of text, extremely long scenes, or scenes that jump around too much and fail to form comprehensible sequences.

Are any of these suggestions things you intend to add to your script?

Do you have any other pieces of advice on pacing?

Let us know in the comments, and good luck with your next project!

Hello, Mr. Taylor. I’m pleased to meet you. My name is Dwayne Pagnotto. I am a great big fan of pirate movies, and about 5 to 7 years ago I wrote a pirate story with the intention of one day having it made into a movie. For this reason, I placed many fight scenes and special effects sequences within this story. While writing the story, I was not aware of the three-minute rule when it comes to action scenes, and as I said it was a story, so of course it did not really apply to what I was doing at the time.

However, in my attempt to fully flesh out the characters’ methods of fighting, and to make the fight scenes sound extraordinary, I went on to practically describe each and every move during each of the character’s sword fights. So that each fight scene follows a very strict course of action, interspersed with dialogue between my main characters and whoever they happen to be fighting with at the time. The concluding scenes of these fights, in turn, lead to each inter-related follow-up scene between the secondary characters, and the main character, the protagonist, or the other stand-by characters who witness these fights, or play a very minor role in whatever happens afterwards.

So, in other words, each little bit of dialogue and action that I have worked into these fight scenes are totally necessary in order to lead into each follow-up scene in a logical and conclusive manner. And these scenes in turn lead into each after-fight scene, which forms the basis for my story.

My question to you is, in such an epic-blockbuster, action, adventure movie, that I have planned, could my way of doing things not be overlooked by whoever reads my as yet unformatted screenplay, in order to keep my movie plot coherent and allow all the scenes to play out exactly as I have planned them?

Because doing so, is vital to have my movie be the huge box-office smash that I have written and planned for it to be.

My movie is called The Dead Sea King.

I thank you sir in advance, for any help and advice you can give me.

Respectfully yours,

Dwayne

Hi Dwayne,

Thank you for the question, it sounds like an interesting project! For something like this it sounds like you would need funding from a large company. If you’re sending your script out to studios/managers/agents having a properly formatted, easily readable version of the script is the best chance at getting a follow up email.

Unfortunately people in these positions are extremely busy and are far more likely to say no to a project so it’s best to not give them a reason. Well over 90% of scripts are passed on, and even out of those that are optioned or bought, only about 10% are made into films.

That said, there are a lot of ways to sell stories. Having a properly formatted screenplay is a huge help, but so is having a treatment, pitch deck, sizzle reel, established IP (intellectual property. For example, if your pirate story is a published novel or based on a true story that’s a boon).

At the end of the day, when you are reliant on others to package and fund a project you will have to cede some control as a writer. Certain scripts have far more action than others, but keeping it in the correct format is borderline essential in getting it read, seen, and (fingers crossed) sold!

Hope this helps,

Cade

Thank you so much for that fine advice my friend. I do have the proper screenwriting software downloaded and I am trimming it down somewhat. But it’s so hard to get rid of all these awesome lines and ideas I have included. But I will do my best.

Thanks once more my friend.

Best Regards,

Dwayne