When first starting out as a filmmaker or videographer, the terms script and screenplay might have confused you. Both are used almost interchangeably, so does that mean they are the same thing? If not, what is the difference between a script and a screenplay?

A “script” is the written document version of a visual art form and is used across multiple mediums, while a “screenplay” refers to a script specifically for movies or television. When you read a script, it could be for a play, movie, television show, comic book or video game, while a screenplay is specific to movies and tv shows. Each script has its own formatting rules to help you tell what type of script it is; whether it’s a screenplay, teleplay, stage play, or something else.

But first, what is the origin of the term “screenplay” and when did it come to exist?

What is the origin of the term “screenplay” and how is it different from a script?

The origin of the word “screenplay” started around the 1940s, but its origins and source are notoriously hard to track down – at least, according to most film historians.

While you would think the term “screenplay” and its format of script would’ve sprung forth naturally from the creativity of writers like other art forms, the creation of the screenplay and its format seemingly came together from a series of practical and technical business decisions.

Essentially, as the popularity of “movers” grew from a novelty side show to their own individual art form, the producers of these productions had to evolve their scripts from simple one paragraph summaries of what happened, referred to as “scenarios”, to something more similar to the screenplays of today by incorporating what’s known as “master scene” formatting.

The blog Screenplayology provides a great summary of literary sources that traces back the etymology of the term and popularity of the format, tracking the transition from these “scenario” scripts into camera-direction heavy “continuity scripts” as productions got more complicated, eventually leading to the development of the “master scene” format we now know.

The master scene formatting divides the screenplay into scenes separated by location; something that’s a staple of modern screenplays and screenwriting today:

[…] whereas the continuity script had evolved to ensure visual continuity and fidelity to a pre-approved budget — the primary concerns of a central producer — the master scene script evolves to ensure readability, serving the needs of the independent producer who must shop his or her script as a property to be financed”

Source: Screenplayology

What’s the difference between a scenario, continuity, and master scene script?

Take a look at this excerpt from the scenario script for Georges Melies’s A Trip to the Moon (which film school students will recognize right away, and non-film school students might recognize from Martin Scorsese’s 2012 film Hugo), written by Georges Melies:

- The Scientific Congress at the Astronomic Club.

- Planning the Trip. Appointing the Explorers and Servants. Farewell.

- The Workshops. Constructing the Projectile.

- The Foundries. The Chimney-stack. The Casting of the Monster Gun/Cannon.

- The Astronomers-Scientists Enter the Shell.

Check out how these first five “scenes” from Melies’ script translated to the actual film, shared here by Youtube-channel Open Culture:

Now, compare the above scenario script to this excerpt from this continuity script for the famous “original narrative film”, The Great Train Robbery, adapted by the director Edwin S. Porter from the play written by Scott Marble:

“1. INTERIOR OF RAILROAD TELEGRAPH OFFICE.

Two masked robbers enter and compel the operator to get the

“signal block” to stop the approaching train, and make him

write a fictitious order to the engineer to take water at

this station, instead of “Red Lodge,” the regular watering

stop. The train comes to a standstill (seen through window

of office); the conductor comes to the window, and the

frightened operator delivers the order while the bandits

crouch out of sight, at the same time keeping him covered

with their revolvers. As soon as the conductor leaves, they

fall upon the operator, bind and gag him, and hastily depart

to catch the moving train.

“2 RAILROAD WATER TOWER.

The bandits are hiding behind the tank as the train, under

the false order, stops to take water. Just before she pulls

out they stealthily board the train between the express car

and the tender.

“3 INTERIOR OF EXPRESS CAR.

Messenger is busily engaged. An unusual sound alarms him. He

goes to the door, peeps through the keyhole and discovers

two men trying to break in. He starts back bewildered, but,

quickly recovering, he hastily locks the strong box containing

the valuables and throws the key through the open side door.

Drawing his revolver, he crouches behind a desk. In the

meantime, the two robbers have succeeded in breaking in the

door and enter cautiously. The messenger opens fire, and a

desperate pistol duel takes place in which the messenger is

killed. One of the robbers stands watch while the other tries

to open the treasure box. Finding it locked, he vainly

searches the messenger for the key, and blows the safe open

with dynamite. Securing the valuables and mail bags they

leave the car.”

Even though it’s essentially just a summary of what happens, notice how The Great Train Robbery’s script looks a lot more like what we know as screenplay format today?

In a more traditional continuity script format, there would be more camera direction dictating exactly what is shown.

That’s because the continuity script format was developed and popularized by the producer Thomas Harper Ince to streamline the production process in the early 1900’s, when producers were primarily in charge.

For more on how the term screenplay and modern screenplay format came to be, check out the wonderful masterclass of an article on Screenplayology’s blog here.

That said, if you want to compare how the script for The Great Train Robbery plays out in the actual film itself, check it below, shared here thanks to Youtuber Old FIlms and Stuff:

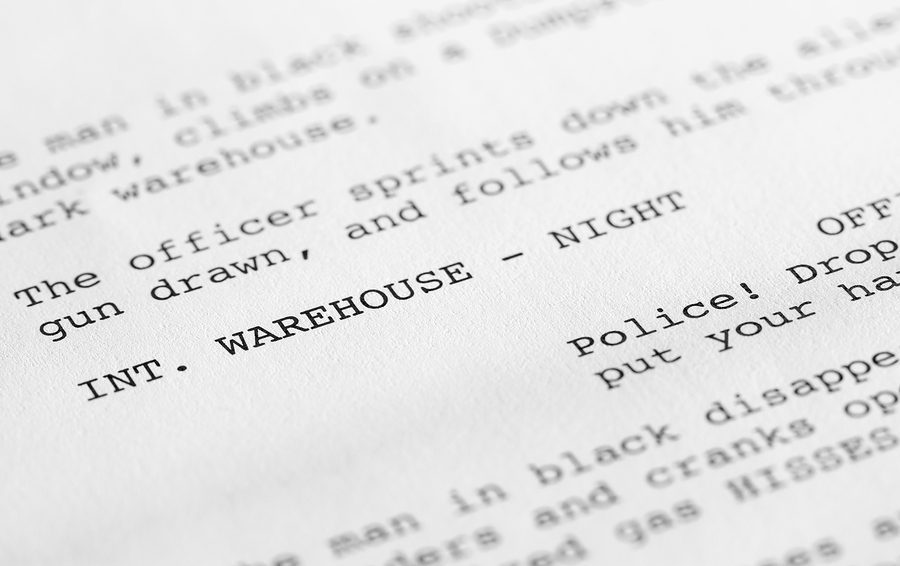

Compare both of these scripts now to this excerpt from a modern day script that follows the modern “master scene” format that all screenplays fall into:

As you can see, in this example, the location of the scene heads the top of the description in what’s called a slugline, with accompanying action and dialogue all folded underneath. We’ll get more into the specifics of formatting later on.

And if you’re asking yourself, “what famous film or TV show is this intriguing scene from?” It’s actually an excerpt from an unproduced pilot I’m writing called Hexagon. No spoilers!

What are the different types of scripts, including screenplays?

The three main type scripts are screenplays, stage plays, and teleplays.

A stage play is a script for the stage, while a screenplay could be for a film, video game, or television episode. And while a screenplay can be for a film or a TV episode, a teleplay is exclusively for television.

While the difference between a screenplay and a teleplay can be kind of confusing, it’s useful to note that teleplay was a term invented in the 1950’s to help distinguish a script from a screenplay and a stage play, and is mostly used today as a technical definition by the Writers Guild of America to separate the writing credits on a TV script for payment purposes.

Example: The WGA will separate the “story by” of an episode of TV alongside the “teleplay by” to account for differences in who wrote the script and who gets credit for the story of the episode, so that they both get paid and credited as necessary. Sometimes it’s the same person!

What does a screenplay for a video game look like?

While most video games do not have traditional scripts that look anything like a screenplay as written above, some of the more high profile, cinematically-styled games will follow a screenplay model of sorts that scripts out the main storyline, or certain cutscenes, as if it were a movie.

For an example of what one of the highest profile video game scripts looks like, check out this example from The Last of Us as shared here.

For games that don’t follow this type of screenplay format, you would be creating something more like a flowchart or spreadsheet with all your various plot narratives and dialogue trees, created in a similar format to this one shared by writer Yun Cheng Hsin.

How long should a screenplay be according to each format?

For a screenplay, the typical rule of thumb is one page equals one minute of screen time.

So if you are writing a half hour TV comedy, you would want your script to be around 30 pages.

Likewise, if you are writing an hour long TV drama, you would expect the screenplay to be 60 pages, and an hour and a half long feature film would be around 90 pages.

If you’re writing a 300 page epic, you might want to write it as a book – or start cutting it down!

That said, screenplays can realistically be up to 120 pages, or two hours, without much trouble. Beyond that, you really have to be a well-known writer for anyone to take your script seriously.

You can read more on the lengths of screenplays in How Long Is A Script For A 2 Hour Movie? And How To Use The Answer In Your Screenwriting.

What about for a stage play?

The general rule of thumb for scripts (one page = one minute) generally applies to stage plays as well.

Still, scripts for the theater can include a lot of action and description per page, which can take longer than one minute’s worth of stage time depending on how they are directed.

That said, if you’re writing a full length play, you’d want to stick to around 100 pages or less to be safe under two hours. Any longer than that, and you’ll probably lose your audience.

What are the elements of a script?

Every script, regardless of whether it’s a screenplay, teleplay, or stage play have the same basic elements. To be considered a script, the written document must include:

- Scene setting: the location where this is all taking place.

- Action: what’s physically happening on screen or stage.

- Dialogue: what’s being said.

- Character headings: who is saying it.

How much direction do you put in the script?

In the old days of continuity and scenario scripts, all that would be described would be camera angles or action.

In the case of modern screenplay format, however, you try to avoid writing camera descriptions if at all possible.

For instance, if you want to indicate that a close-up on a specific object, like a lamp, could be useful, instead of writing “the camera pushes in on the lamp” you would write “Close on: an ornate lamp” or “He notices the lamp – a relic from another time, and out of place.”

What does a screenplay look like?

A script, whether it’s a screenplay, stage play, or teleplay, all start off looking the same. Each begins with a title page that shares the name of the story and the writer, or in the case of a television episode, the name of the episode as well.

From there, the scripts will look different depending on their respective formatting.

For instance, certain teleplays will have Act Breaks on them, as will stage plays, but feature screenplays do not.

For more on how to write screenplay format, check out our article on the subject here.

What if you’re writing the script for a book?

If you’re writing a novel, your written document is still technically a “script” of sorts; it’s called a manuscript, which refers to the content of a novel before it’s formatted and printed as a book.

So if you were writing a novel and wanted to submit it to publishers, you would first send them a query letter (as you should never send your written works unsolicited) and should they respond with interest, you would then send them the manuscript for the book.

If they like it and want to publish it, or if you decide to self-publish, you would then work with a copy editor and/or copy edit yourself to format the manuscript to be printed as a book.

How do I write my own screenplay / script of any kind?

If you want to write your own script, or more specifically, your own screenplay for movies or television, you will need a screenwriting program to help you format it correctly (there are free options as well). From there, it’s all about learning the craft!

For more on how to write screenplays, or more specifically, a screenplay that works, check out our article on the subject here.

If you have more questions about scripts and screenplays, reach out in the comments. Otherwise, check out our other articles on screenwriting, and good luck on your writing journey!

Hey thanks for the information, this was very helpful.

You’re welcome Lance 🙂 Will you be writing a script or screenplay anytime soon?