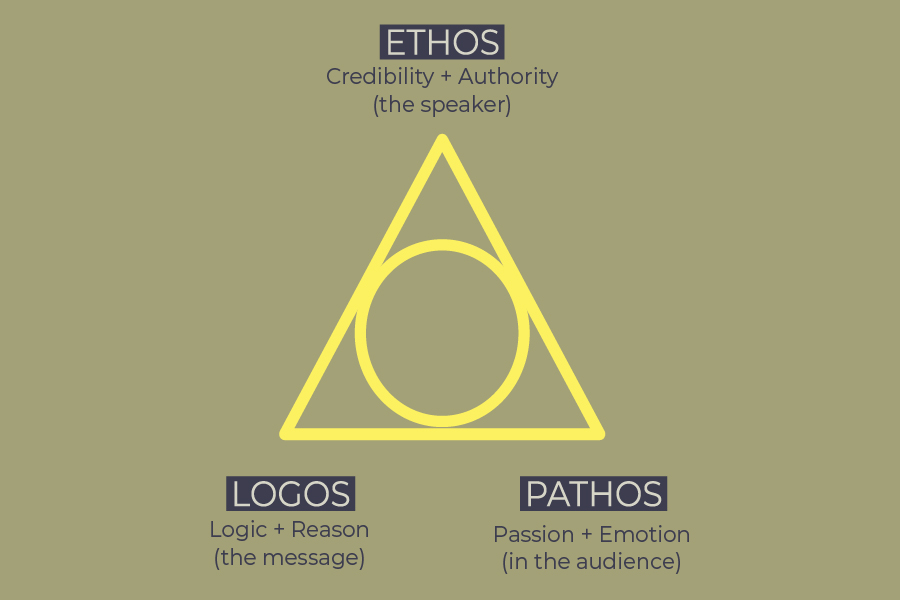

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos are modes of persuasion (rhetorical appeals) used to convince audiences. Ethos refers to the author’s credibility and character, Pathos appeals to the audience’s emotions, and Logos appeals to logic and reason.

The terms ethos, logos, and pathos were coined by the ancient philosopher Aristotle. Together, they make up the rhetorical triangle.

Understanding these concepts is critical to analyzing and crafting compelling arguments, whether in a blockbuster movie‘s climactic scene or a commercial’s punchy pitch.

In filmmaking, screenwriters can use these appeals to build character traits and drive conflict. Or they can be used to write powerful monologues.

In advertising and communication, these modes of persuasion are used to establish trust, connect with consumers on an emotional level, and drive sales or change logically.

In this article, I’ll explore the different ways storytellers and screenwriters use them to make compelling characters the audience connects with and how this can be used to drive conflict.

I’ll also examine how Ethos, Logos, and Pathos make practical tools for compelling arguments in marketing campaigns, strategic communication, speeches, and sales pitches.

Table of Contents

Ethos

The Greek word Ethos refers to the ethical appeal or the credibility of the speaker (or writer).

It relies on the speaker’s character or writer’s credibility to establish authority and trustworthiness.

When you use ethos, i.e., make an ethical appeal, you seek to establish credibility by knowing a particular subject (extrinsic) or presenting your persuasive argument (intrinsic).

It’s how you, as the presenter, convince your listeners you are qualified to speak on a subject.

Ethos examples in marketing or communication

Advertising frequently leverages these persuasive advertising techniques to influence consumer behavior.

Examples of ethos used in advertising include a brand using a trusted celebrity endorsement.

Picture LeBron James flying across your television, his skill implying a sports drink’s high performance. This is ethos in action.

These tactics use the status of famous figures to increase a brand’s trustworthiness, utilizing ethos for persuasion.

It’s not solely about celebrity influence; expert endorsements associate a product with recognized expertise.

When you purchase sneakers or supplements, you’re not just acquiring an item but partaking in a legacy of excellence.

This strategic approach is deliberate, aiming to engage with you—the innovator, the trendsetter, the early adopter—on a level that goes beyond the average.

You can also act ethos in infomercials about important topics or a documentary featuring a respected expert.

Ethos may change over time.

Notice also that ethos is connected to the personal character of the speaker, and how the speaker is perceived may change from one demographic to another or over time.

A politician such as Donald Trump is an excellent example of a controversial figure who is highly trusted by one demographic and distrusted by another.

We see how ethos is valued differently over time when fx a celebrity gets into trouble.

A good example is the Johnny Depp vs Amber Heard trial, which had severe consequences for both celebrities – financially, job-wise, and reputation-wise.

Another example is Will Smith’s slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, which saw Smith’s popularity decline, projects being put on hold, and has led to a painfully slow recovery of respect in the public eye.

Ethos examples in movies

In feature films, ethos can be used to measure how well your film convinces your audience of the story’s credibility.

For instance, ethos is evident when a character’s backstory reveals their expertise or noble qualities, enhancing their credibility.

A compelling use of ethos can be seen in courtroom dramas or films about great trials, where the integrity and credibility of characters are pivotal.

A character with ethos is Harry Potter, i.e., the offspring of powerful wizard parents, which helps establish his credibility as a powerful wizard from the beginning of the story.

Throughout the series, he consistently does “the right thing,” meaning he always makes the ethical choice.

Logos

Logos represents logical appeal. This involves constructing logical arguments with clear, rational ideas and common sense, often employing deductive or inductive reasoning.

Logos appeals hinge on presenting a logical conclusion that makes sense to the audience, steering clear of logical fallacies.

So, Logos appeals to a listener’s logical reasoning, usually by incorporating supporting facts and figures to support the claim.

Logos harnesses the power of evidence to construct an unassailable case for why you need that gadget, service, or innovation.

It’s the backbone of a strategy aiming to engage your intellect, not just your emotions.

When wielded effectively, logos transforms complex data into clear, actionable insights, effectively guiding your decision-making process.

Logos examples in marketing or communication

In advertising, logos frequently appears, utilizing hard data and rational arguments to persuade you of a product’s value.

In the era of data-driven marketing, persuasive statistics serve as a central component.

These aren’t mere numbers; they tell compelling stories through data that appeal to your logical thinking.

Imagine an ad for a data-driven solution for digital transformation in a large corporation. In such a campaign, the use of logic and the use of facts are important to convince the decision-makers to buy the product.

Logos appeals in advertising are visible in ads that present logical arguments or statistics to validate a product’s effectiveness.

Advertisements for medications, for example, might include scientific data or logical explanations of how the drug works as a means of persuasion.

Or picture a new gadget with better specs than the competition.

If you want to compete on specs, raw data is a powerful tool.

Logos examples in movies

In film, Logos is the presence of story logic.

Story logic connects each beat of the story to flow naturally to the next so the viewer can draw conclusions and determine that everything makes sense according to the story’s world.

Logos is also used in films that hinge on strong arguments, where the narrative leads the audience to a logical conclusion through literal analogies and open-ended questions.

A movie featuring a detective piecing together clues showcases logos by guiding the audience through deductive reasoning.

A good example from the feature film is Harry Potter’s friend Hermione Granger, who embodies logos. She’s the brains and the perfect student, and she approaches magic with logic and reason.

Pathos

Pathos is the emotional appeal, targeting the audience’s emotions. The word Pathos means suffering or experience.

The common use of pathos can be seen in commercials that associate products with positive emotions or societal ideals, such as a sense of belonging or happiness.

Pathos appeals leverage emotional response through meaningful language and emotional tone and sometimes evoke empathy with powerful imagery.

Examples of Pathos in marketing or communication

Modern commercials use pathos to captivate your emotions, creating a memorable association with the brand.

These ads tell stories that stir your deepest emotions, making you feel more than just a viewer.

The most effective commercials elicit a true emotional reaction, motivating you to act, share, and stay loyal.

Brands excel in crafting empathy, allowing you to see parts of your own life in their stories.

This connection elevates a simple product to an indispensable part of your life.

Pathos is not solely about emotion; it’s about establishing a memorable link between you and the brand.

Examples of Pathos in movies

Pathos is often the driving force in filmmaking, stirring strong emotional responses through storytelling.

A poignant example is the use of climate change imagery in documentaries, which creates a powerful emotional appeal to spur viewers into action.

In the case of feature films, pathos is a measure of how your film persuades the audience to invest their emotions in the story’s world.

Harry’s friend, Ron Weasley, embodies pathos in their friendship triangle in Harry Potter. He is passionate and always there for Harry.

Ron is funny, brave, insecure, immature, and jealous. His love and feelings for Hermione are often not mirrored by Hermione, who is both more mature and rational.

Combining Ethos, Logos, and Pathos in marketing and communication

Combining ethos, logos, and pathos is an effective strategy for making effective arguments.

An example of Pathos in a strategic communication campaign is a TV spot with a family involved in a horrible car accident due to speeding.

This is a good example as it utilizes all three rhetorical appeals. The sender (a government entity) wants drivers to slow down ethically.

Pathos invokes negative emotions such as disgust, anger, fear, and maybe even guilt.

This may lead to the logical conclusion (my family might get hurt, or I might hurt somebody) that it’s better to make the ethical choice to slow down, thus driving change.

Combining Ethos, Logos, and Pathos in Film

Film directors, authors, and screenwriters masterfully employ these methods of persuasion to engage viewers and drive conflict.

Many conflicts between Harry Potter, Hermione Granger, and Ron Weasley are driven by their character traits based on the three rhetorical appeals.

Take, for instance, the conflict between Ron and Hermione over Scabbers and Crookshanks.

Ron accuses (Pathos) Hermione’s cat Crookshanks of being responsible for the deteriorating health of his rat Scabbers, while Hermione argues (Logos) why this isn’t the case.

Their emotions run high over this issue, resulting in a period where they cease communicating for several weeks, with Harry (Ethos) intervening in an attempt to reconcile them.

Closing Thoughts

Ethos, pathos, and logos remain critical tools in the arsenal of modern storytellers, from filmmakers to advertisers.

By harnessing ethical, emotional, and logical appeals, creators can craft messages that resonate deeply with their audiences.

As we navigate a world saturated with messages vying for our attention, the ability to discern and employ these persuasive techniques becomes increasingly valuable.

If you found this article useful, you might like Hyperbole: Definition and Examples from Film and Literature.

This is verrry useful and helpful for I havent a clue how to work my film analysis around this trio. Thanks heaps.

Hi Badrul.

We’re glad to hear you found it useful. Good luck with the analysis 🙂

Best, Jan